- Details

- Written by dave

- Category: Korean War

- Hits: 3757

Long Patrols

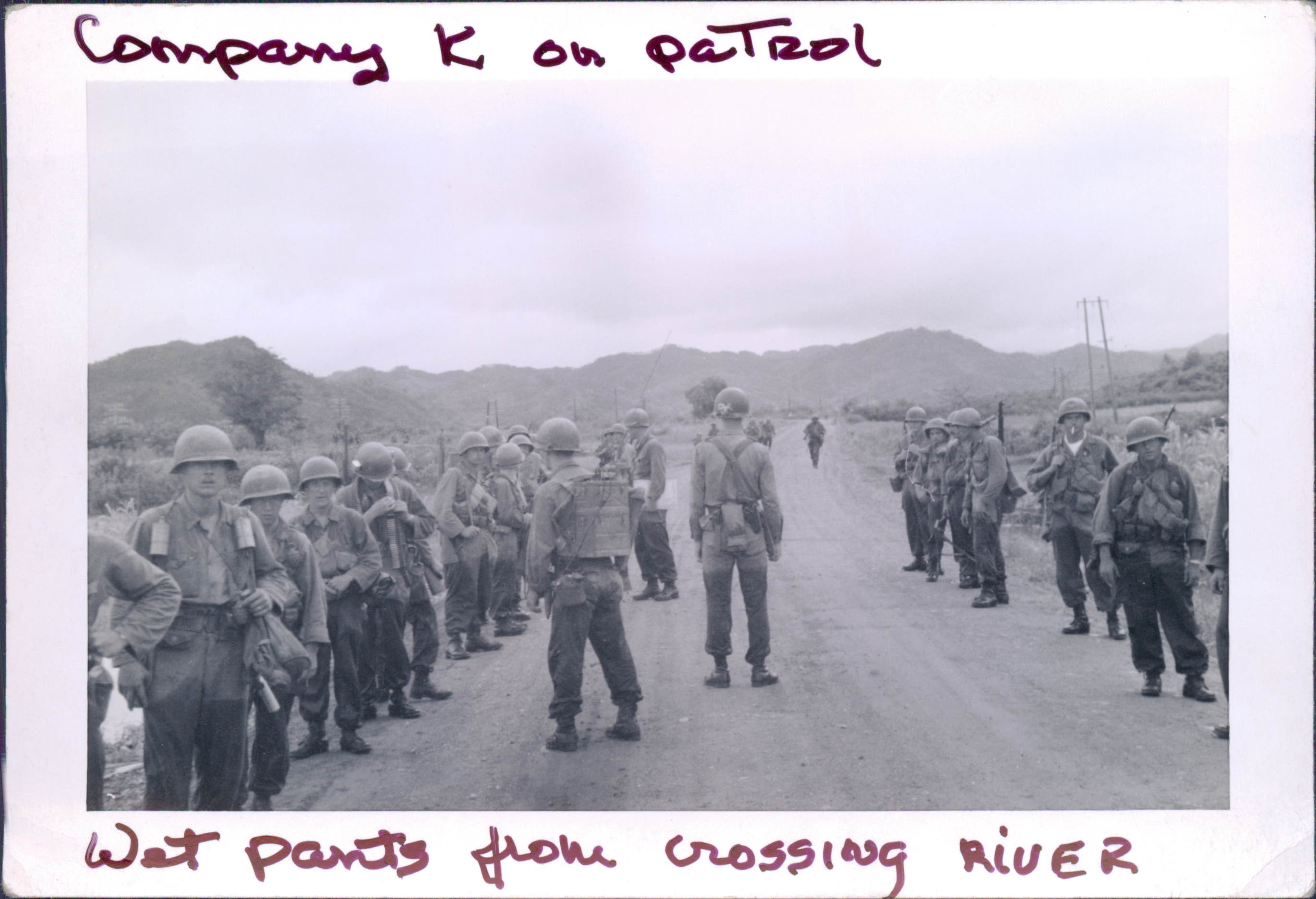

Before attacks were launched against the Chinese Army in the western half of Korea, the 1st Cavalry Division sent out a whole series of Patrols over quite a span of time, into April. The Chinese had pulled well back and the 8th Army Intelligence wasn't sure where they were, just what they were up to, or what kind of units were there.

So I was picked to do a long patrol where others had failed to find the enemy.

After it was over I sat down and wrote an account of it to my mother. She passed it on to the Denver newspapers, and they printed large gobs of it.

Here it is, verbatim. I wrote it on April 1st, April Fools Day.

April 1, 1951, Chunchon, Korea.

Dear Mom:

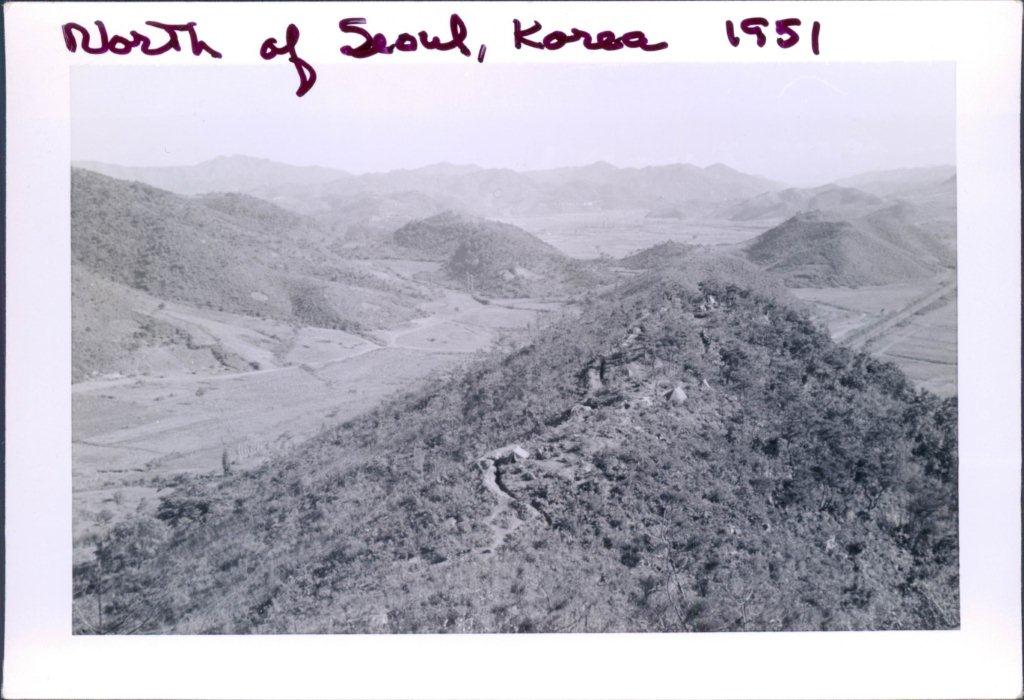

Again from a mountain peak, this time the highest ever, Hill 899, a mountain almost 3,000 feet from valley to peak.

The Marines are to the right of us, and the Chinese are in front of us.

I have a rather interesting story to tell about our last, and

most successful patrol -- a patrol deep into enemy territory.

We had been sitting on a 650 meter peak overlooking Chunchon and the Song-Gang River for several days, while patrols attempted to cross the river to find the exact enemy positions.

But all of the patrols had returned, saying that the river, a swift channel 200 feet across, was unfordable. And that the Chinese had it covered with machine guns.

But the information was vital and so they sent us, Company K, saying, "You will cross the river." An order.

We set out, my 50 men and I, with a mortar, a 57 MM recoilless rifle a map and a mission. We started at six o'clock in the morning with the mountain fog so thick that one could not see the length of a squad. Our final objective was a mountain peak six miles away, over four intervening mountains) a gauntlet of enemy top ridge machine guns, a deep valley with a 200-foot river without boats or bridges -- and a record of five other patrol failures to reach that objective.

By ten o'clock our radio reception was too weak to keep us in touch with our friendly lines.

We plugged along through the fog, over ridge after ridge, after ridge, hoping our compass wasn't being affected by the ore in the mountains.

Finally I looked at my map and decided we were on the right peak, and so we began the long descent down a deep slope through jungle- like undergrowth.

But when we reached the bottom and cleared the fog, I realized that the valley went in the wrong direction. Suddenly a South Korean appeared out of nowhere and began jabbering wildly. After listening for a little while to a mixture of Korean and Japanese lingo, we realized he was trying his best to tell us we were very close to two machine guns of the Chinese, and that they had ambushed a previous patrol just two days ago. I saw then that we were one valley short of our route, so -- with a long look at the tiring men behind me, I started up the long, long trail.

By noon the fog had lifted and we were back on the right ridge, ready to drop down again, 1,500 feet to the river below, I ordered a short break, we gulped a C-Ration, and in fifteen minutes were on our way.

We had brief contact with an artillery liaison plane who carefully looked us over beore we convinced him that we were G.l.'s deep in enemy territory.

On the way down the mountainside one man dropped his helmet, and it rolled 1,200 feet before stopping at the river's edge. Well announced to the enemy by the rolling helmet, we reached the water's edge by one o'clock, and after a short search of the area we set up a mortar, cannon and machine gun to cover our crossing, lest some well-placed sniper pick us off in the water, and, with a prickly sensation at the back of my neck, I started wading across the river. The cold water went up, and up, and up. Soon it was up to my chest, and I was unable to move for the current. We just couldn't do it here, so I ordered the platoon back to the shore.' But luckily for us, an old Korean came wobbling down from his wretched house, and without a word, beckoned me to follow him down stream.

He went about 100 yards and then pointed to a lone tree on the other side. I understood; it was an old Korean route across on a hidden sandbar.

We started out again, and this time just as the water reached my neck, I felt the slope go up and I was soon on the other side. The platoon followed, but it was apparent the short men could not make it. So, leaving ten men on the south bank to secure the crossing, we headed north again, dripping wet, and shivering in the bitter wind.

However, one forgets physical discomfort soon when operating in enemy territory, and the late afternoon sun began to quell our trembling after a while.

We had been going for eight hours steady now, and some of the older men, and the "unhardened" replacements were almost exhausted. I urged them on till we turned up the last long valley to our objective. That could really be a trap, so I dropped the tired men here to secure the mouth of the valley, and hurried up the final mountain with the last two squads.

I was reasonably sure there were no Chinese on that particular peak, and after seeing how late it was, I drove up the mountain without caution as the men straggled out behind.

It was then and there I thanked my Colorado mountain Up-bringing and West Point physical training that had prepared me for such a life .

Five of us gained the top by three PM and no enemy was present. There was another peak towering above us, however, that was suspected to be occupied by the enemy, and if our mission were to be entirely successful, we should be able to tell Headquarters if the enemy were there or not.

There was one risky way to find out, so I gathered all of the squads together on the very top of the peak, in an exposed position, and began milling around, preparing a good target.

Sure enough, in a minute we heard a Brr Brr Pop Pop and bullets started whizzing by. We jumped for cover, fired back, and I started to radio back to the company.'

Then we discovered that the radio had shorted out completely in the water and was useless.

I marked the enemy positions on the map, lest I become a casualty, and ordered the withdrawal. It was then I noticed that we were only a few thousand yards from the 38th Parallel.

I then I announced it to the men, one of them fired a round from his rifle in the general direction of the boundary line, and muttered something about l'll get something across that Parallel, anyway!"

We clambered down that mountain as fast as we could, for our mission was not to fight 'em, but to find 'em.

All the way down the mile long valley the Chinese sniped at us but we suffered no casualties and soon got to the river, picking up our outposts as we went.

The return across the river was sure to be more difficult because we had to push upstream against the current.

So three of us, armed with poles, set out dragging a long piece of Chinese communication wire behind us in order to make a sort of guy-line till the last man, Pfc. Gingles, from Abilene, Kansas, lost his footing and started to drag the two of us down stream. He finally got loose from the wire, but weighed down with an 18-pound automatic rifle, and a 15-pound ammunition belt, he began to tumble end over end down-stream.

Then the drag on the line became too much for Pic. Lewis and me and we began to get pulled off the sandbar.

Gingles got free from his equipment and tried to make for the shore, but when he saw Pfc. Lewis slip under the water, he yelled. "Lewis can't swim". and turned boldly back into the stream. I was all fouled up in the wire. and between my steel helmet my heavy boots and clothes. I quickly went under.

In a minute we would be swept into the narrow rocky curve below and into an area where the Chinese had their guns over the river.

Somehow I got loose from the wire and shed my helmet. and after endless swimming and banging along under-the water I reached a shallows, where I stood up to look for Lewis , He had gone under several times and was gasping and gagging, but Gingles had managed to pull him toward the shore, and by this time the men that we had left on the south bank had made a chain out into the water and dragged both of the men to safety.

The three of us lay for a while, utterly exhausted -- Lewis was unconscious the patrol was split -- and we were still five miles from our lines, with the enemy knowing of our presence.

To add to the bad situation, our only map had floated away downstream. It was then four-thirty in the afternoon, and night would soon be upon us. There had to be another decision, and quickly.

I shouted across to my platoon sergeant, Master Sergeant Carl Irvine, of St. Joseph, Missouri, to take his part of the patrol down the north shore about three miles to where another Battalion had made a crossing several days before.

My half of the patrol carried Lewis to a covered draw and we

built a roaring fire, which helped to revive him, and also to take the cramps out of our aching limbs.

As soon as possible we set out for our lines, and I tried hard to remember what the map looked like in this sector.

Just before darkness closed in we reached the top of a commanding ridge, and I glimpsed a familiar looking peak in the distance.

We set out in earnest, tired to the very core, but knowing that our safety lay only in movement.

The other half of the platoon had set out immediately and by dark had surprised an enemy patrol, dispersing them; had contacted a friendly patrol, radioed our predicament back to our lines, and re-crossed the river on an underwater bridge to safety.

We were in trouble though. We slowed to a crawl in pitch darkness as we tried to make our way along the high cliffs and ridges. But about eight o'clock the U. S. Army began to operate to help us on our way back. Knowing it was useless to send out patrols over the vast expanse of mountains, they relied on artillery and searchlights to help.

The first thing we saw was a powerful, wide searchlight beam shoot into the sky over us and light up the whole area, with the glow reflected back to us from the cloud base. Then another beam shot up.

We were able to move faster. Then we heard the ominous whine of an artillery shell speeding toward us.

We jumped for cover, thinking we had been spotted by the Chinese or mistaken to be Chinese by our own units.

But as we waited for the deafening explosion, there was a welcome "POP, and the bright glow of an artillery parachute flare lit up our path. Then we knew we were O. K. -- and with the help of searchlights and flares, crossed the welcome challenge of our company outpost at eleven-thirty P.M., after seven teen and one-half hours of grueling combat patrolling.

I phoned in a complete report to Headquarters, and was told

that we had done an excellent job of getting all the information needed on which to plan future operations.

That was my reward.

The reward for my men came a few minutes later when it was announced that hot coffee and cinnamon rolls had arrived from away back at our field kitchen, where a cook had been "sweating out" our return.

The lusty shouts that went up heralding our return must have

disturbed even the impassive Chinese leering at us from the far off hills to the north.

Love,

Dave

- Details

- Written by dave

- Category: Korean War

- Hits: 3795

My First Real Combat Leadership Test

Gen Ridgway started his offensive efforts by a series of limited objective probes of the Chinese defenses North of the Han.

Company K, as part of the 3d Battalion was given the mission on the 10th of February to climb to a series of ridges ''in their zone' and press on toward the Chinese lines to determine their strength and defenses. The 1st Platoon led all the way to the closest small summit without being fired on or gaining any other contact, Captain Flynn ordered me to pass through the 1st Platoon's position, and continue advancing along the knife-like ridge which appeared to be punctuated by a series of small peaks, the next one being a little higher than the one he was on.

Flynn. with his radio operator, and two forward observers, one for Company K's 60mm mortar section, and the other for Company M’s 81mm mortars further back at Battalion stayed on the small summit and could watch my platoon’s progress. He told me they could not see any enemy positions or movement, even with binoculars. I was to move along the ridge and report back if I spotted any enemy positions. That if I went 1000 yards with no contact, the 3d Platoon would pass through me. With a typical Flynn Irish grin he wished me good luck.

Well I was immediately faced with the classic Korean ‘narrow ridge line’ conundrum. If I had my platoon go single file along the ridge, which was no more than one-man wide, and we were fired on, my point men would take the brunt of the punishment before I could get following units into position to fire back. If I tried to move too far down off the ridge their travelling would be very difficult and slow.

So I punted. I told the 1st squad and 2d Squad behind them to continue to move up the ridge line toward the next low peak about 150 yards ahead. I told the third squad, with the weapons squad behind them, to walk parallel to and abreast of the 1st squad but down on the side hill only about 5 yards. That I would be behind the 2d squad to coordinate the four squads and report back to Flynn.

We got about 100 yards when all hell broke loose with at least one automatic weapon from the very top of that first peak. At least two Chinese were there, hidden with branches and twigs making them look like part of the hill, firing right down the ridge. Everybody dived for cover, and several returned fire. Within 10 seconds, I could see one of the Chinese soldiers jump up with the light machine gun and fall back down over the peak and go out of sight. The other one didn’t move that I could see. Firing stopped from the enemy. Nobody was hit in my platoon.

There was certainly ‘contact’ – the ridge had enemy on it, but where? I went forward to our point man who was flat against the earth, his weapon pointed at the peak. Nobody shot at me while I moved forward in a crouch I was pretty sure both Chinese had bugged out. I got two men and we carefully approached the peak. Both Chinese soldiers, who had been there, had indeed fallen back along the ridge.

Right then a burst of machine gun fired ripped past me, somewhat exposed. It came from the next peak, high point. I called out to the third squad to go around those firing and lay down a base of fire while the 1st squad rushes the peak where the firing was coming from. I then called Flynn and told him the situation but that unless we drove the Chinese off that second peak that they could fire down on our men trying to withdraw. He agreed.

So I motioned, yelled an ordered the 1st squad to assault the top of the hill when they hear the firing from the other side of the hill.

Neither squad seemed eager to move. I got down to the right where the 2d squad was and told them to open up on the peak. Only two or three men started firing.’

I should have moved to the left down to the 1st Squad and went with them to the top. But I didn’t. And they weren’t moving, just staying under cover.

I was frustrated. I didn’t know how to get the Jail Bird platoon to move. I felt like I was pushing wet spaghetti. And any minute the Chinese could get aggressive and rain fire down on both sides.

I stood up, told the 3d squad to cover me, and I charged up to the top of the peak, alone, firing at it with my carbine as I went. Suddenly I was on top of their parapet and I fired down at all three there before they had time to swing their machine gun around towards me. They were still aimed down at the 1st Squad’s location. I either killed or badly wounded all three for they just lay there. And I started firing at several others now running away toward the next ridge a long way away.

Sgt Ingram who had my radio came along the ridge forward and yelled that Capt Flynn wanted me to pull my platoon back, that the mission was accomplished.

I yelled down to both the 1st and 3d squads and told them to get back to the Company OP, that I would cover them.

The Chinese did not follow up, they just fell back toward their further units, nor did they open up on me.

When I got back to Flynn's position, he noted I had a gouge out of my helmet where a round struck it, probably from that first machine gun burst.

Both he and his First Sergent seemed changed in their attitude toward me. I was still hot with my inability to get my Jail House Platoon to attack. I had a lot to learn. I was the last man back off that hill.

I soon found out what had changed. Battle hardened Capt Flynn put me in for a Silver Star for my solo charge. occupation of the machine gun nest, and killing everyone there - which he watched through his binoculars.

I for one had mixed motives. While it was encouraging that I was recognized for getting the job done, I was angry that I couldn't get my platoon to do it. I had to do it myself.

My platoon seemed to take me more seriously after that February incident.

I had passed the test as to whether I was willing and able to do anything I ordered my soldiers to do, while under fire.

(See First Silver Star under this link'

- Details

- Written by dave

- Category: Korean War

- Hits: 3644

My Voice is Heard Again

After Hill 578 we had a break long enough for us to recover, replace broken or lost equipment, and take stock of where we are, individually.

I wrote a long letter, as much to myself as to my Mother. Here is that April letter.

Lt. David R. Hughes

Mrs. Helen Hughes

Shirley-Savoy Hotel

Denver, Colorado

Korea

Dear Mom:

I was cold, wet, miserable, tired, hungry and discouraged

a few minutes ago, when I saw some sturdy soul come trudging up the

mountainside with mail, Now, I am only cold, wet, tired and hungry.

Your letter gave me a great lift in the midst of all this chaos

and confusion.

I am now well down in a foxhole on the top of the highest - I

swear - mountain in all Korea, except, of course, for the one we were

over yesterday, and the day before, and, the day before that. We

gallant cavaliers of the First Cavalry are trying to break the backs

of the Chinese right now, and upon the reflection of the last week. I

do not see how the bodies and minds of men keep going so long without losing their elements of control and composure.

I do not kick too much for myself, for all I must carry is weapon,

ammunition and rations - but these men of my platoon. who must stagger up the slopes with 40 pounds of machine-gun ammunition - and the machine guns - and the rockets only to be shouted at, shot at, and cajoled into running the last fifty yards through machine-gun bullets, grenades, mortar fire - are men of the highest discipline. And discipline for what?

To be carried off the hill by four other men, and suffer smashed heads

and broken bodies, thinking they are the unluckiest men in all the

world until they see the dribble of others into the Aid Station with

their heads smashed in a little deeper, and their bodies broken a little

more? I don't know. It's hard to see the forest for the trees here.

And it is a question greater than all questions, when I look over

that hill and watch the placid face of the Chinaman, with the flap-eared cap on his head and the quilted coat, and wonder what he is thinking, and - what is more important •• why he is thinking it.

In an hour or so I will be there where he is, and he will be dead,

with a hole in his head much larger than you would expect from my little .30 caliber rifle. That he will be dead, I am very sure, because I have confidence in my men and in myself.

As I have been writing here, six men (two from my own platoon) have

passed my foxhole, hit by a mortar shrapnel. They are on their way

down to the Aid Station ... and rest - some for weeks, and some for months.

I wonder sometimes how much luck there is to the game, Or is it

luck? And is it a game? Back on Big Hill 578 we got pinned down close to a strong position, and they grenaded us. I was lying in the open when they yelled 'Grenade so I rolled over and felt something against my leg - looked down just in time to, see the handle of a potato masher grenade against me. Blam! The handle of the thing gave me a real Charlie Horse and a bum eye for awhile. But not a puncture in me any-where The man next to me was killed by it.

What is the answer? Luck? Prayer? I won't even hazard a guess.

SOMETHING is making it possible to live. And yet I would rather be here than anywhere in Korea now. It is life in its rawest form. It reduces sham to NOTHINGNESS, and here men are themselves. Here the values of life are returned to us; the simple act of making a cup of coffee is a worthwhile accomplishment. As a leader of 40 men I have the good feeling of responsibility, and aside from the close-in fighting, it is for me to provide many of their needs; minister to their hopes and fears; raise their morale; deal with their misbehavior; listen to their feelings as they express them; and try to direct their lives so that they will function with a will and a purpose.

There is no democracy on a hilltop; but as a platoon leader, there

is no troop leading quite as intimate or as thorough; and it is a

responsibility. There is no officer below to pass the buck to. What more could one ask in the way of service to those of lesser rank? The only guide I must religiously keep, is the principle of humility; decide with confidence; lead without fear; listen with compassion; and remain humble.

It is a far greater, more rewarding life on this hill, Mom, than all

the successes of what we call 'Civilization'. Mahatama Ghandi said once, about this business of leading, and very accurately. "There go my people - I must hurry and catch them, for I am their leader."

Korea is tough, but what worthwhile reward is gained without some price? Perhaps now you can see why I chose West Point. If not, someday I will explain. Since I have discovered an important truth, I suffer much less. That is, that fear is only the emotion of ignorance. If I keep informed, fill the gaps of knowledge with educated guesses, fear disappears - andI can do my job as coolly as tho I were in Denver.

And that's all from Korea today.

Love,

Dave

She gave it to the Denver Post, which reproduced it, full text.

It got picked up many places. The Rocky Mountain News - competitor to the Denver Post, picked it up also and printed it full text.

The Chicago 'Rush Limbaugh of its Day' Alex Drier read it aloud over his nationally syndicated talk show.

Acme Steel News - a national Steel Industry Newsletter reprinted it in its slick publication.

The Valley Forge Foundation, gave me an award for it and cited it for its 'contributing a better understanding of the "American Way of Life"

Finally, on August 9th, Senator Eugene Millikin of Colorado, who had appointed me to West Point, read it aloud on the floor of the Senate - in, according to the Rocky Mountain News - a 'voice choked with emotion'.

It was then entered into the Congressional Record.

- Details

- Written by dave

- Category: Korean War

- Hits: 4308

Big Hill 578

Having determined where the bulk of the Chinese Army units were from a series of 'Reconnaissance in Force' patrols Gen Ridgway determined that Hill 578 was important to be in 8th Army hands before any moves past it deeper into Chinese controlled areas could be risked.

The fight for Hill 578 became the first battle against a well dug in enemy on a large mountain that I got involved in.

It took all four battalions of the 7th Cavalry to acccomplish that mission - which included the Greek Battalion that had won its spurs in late January on a series of smaller hills which were fiercely contested.

The Chinese were on the top of 578 in force. They had had time to fortify the top of the mountain.

The operation was to be proceeded by heavy bombardment by artillery, heavy mortars, and several air strikes with 1,000lb bombs.

Then the first attempted assault on the top of the ridge by the 3d Battalion was to go up a quite steep approach route on the west side of the mountain.

Short Round

Such a battle was bound to produce errors in indirect fire. I came very close to losing my life when I found myself and my platoon pinned down from fire from atop the west side slopes of 578.

I was lying on the ground my face almost pushed into the dirt to get lower than the direct fire coming from the top, when I got word that several barrages of large 4.2 mortars would be incoming to try and supress the fire from on top.

We were told to stand by and wait until after the barrage was over, perhaps 24 rounds.

The Sound of Incoming

Now by this time in this war I was getting used to telling what caliber mortar rounds 60mm company fire, 81mm battalion fire, or heavy 4.2inch rounds were incoming by the sound they made coming down.

A 60mm mortar shell comes down whiz-bang. Unless you are within 10 yards of that your chances are good of not getting hit. But you also can't beat it to the ground when you first hear it whizzing down.

A big 4.2 inch mortar round - or the Chinese equivalent 120mm, comes down with a whisper-whisper sound that starts so high up, if you hear that and flatten yourself, the chances are you won't be hit unless it is close.

But the 81mm (82mm Chinese) is the real man's weapon. It whistle bangs fast enough that only if your ears are cocked to listen for it - perhaps because you hear the chug-chug of the mortars coming out of the enemy tube about 10 seconds before it starts down, and you hit the deck fast, you might evade being hit.

I got very good at telling what was going on, especially at night, by the sounds the various rounds made. I also developed a bad habit, when I heard incoming mortar fire, of yanking my helmet off so my hearing was more acute.

Bad Round

So when I and my platoon were flattened out on the slopes of Hill 578, waiting for the 4.2 mortar salvos, ONE round was a dreaded SHORT round. It whispered its way down and hit less than 3 feet from me! But it was a dud, a bad round that was also short of its intended target. It dug a hole but the tail fin broke off and tumbled hitting my left arm, leaving a scratch on my arm and a sore bruise. No other injury. BUT had that 'short round' been good ammunition, I wouldn't be here.

Continued Assault

After the salvos were over, we continued up the hill firing while being fired at. The prepatory fires had done their work. So many Chinese soldiers were killed in their foxholes that we seemed to outnumber them as we neared the top. And they could still throw grenades.

Fortunately their grenades are crude, compared with the 'fragmentation' US Army grenades. Sometimes they just break into two or three, rather than 10 or 20 and you won't get hit unless you are in the path of those two.

I got my first Purple Heart when one of their 'potato-masher' grenades landed next to my leg, went off, but the iron end went away from me, while the wooden handle slammed my leg, giving me a painful bruise, with some blood that had to be staunched and cleaned by a medic when I limped past the aid station coming down a hill.

Then came one of the defining moments in my life on Hill 578.

My Obsolete Thompson Sub-Machine

My platoon guys were spread out crossing a series of foxholes with dead Chinese in them and firing on further hiting those who popped up. i.e. we were making progress working through a wide maze of defensive works.

I was behind the line of them, holding my radio in one hand and my carbine in the other when I heard a sound behind me, I turned to see a bloody Chinese soldier rise up and start to aim at me. He fired and missed. I fired and missed. But my carbine then jammed as its automatic light action couldn't seat the next .30 caliber shell! I had to yank it back and jam it forward again while he took a bead on me, again. My second shot killed him.

But at that instant I lost all confidence in that light officer's carbine. It can't handle the blown dust and grit on the typical Korean hill top that has been pulverized by prepatory fires.

I walked over to the foxhole where that Chinese soldier, and a second dead one was in the bottom of the hole were. I saw a Thompson .45 caliber submachine gun on top of him. I reached down and got it. It still had a magazine about half full in it.

From that moment on I carried that submachine gun with me and got rid of that carbine. It was obsolete according to the US Army. They issued something called the 'Grease Gun' to replace it. I hated that one.

Ironically the Thompson, our WWII Army issue sub machine gun, was given to the Chinese Nationalists after the world war. After Mao defeated them those weapons were carried into Korea by his communist Army. We were fighting against our own American weapons!

But the heavy bolt action on the Thompson would crunch through grit and always seat the round. So after the fight on Hill 578, I put a sling on it, over my shoulder so it would hang, its muzzle aimed at the belly button of the man in front of me. And I kept the verticle rather the round drum magazine below to balance it. I hung it on my side, so could fire it left handed. (Only problem was that a Thompson is made for right handed shooters. So the slide with a projection for your hand to push it back comes back on the right side. When I fired it from my left side that damned handle would repeatedly gouge my hip bone. I had a sore hip for a long time after I was out of Korea)

Finally, the strike of that heavy .45 caliber slug made such a dirt puff on the kind of hills we kept climbing and assaulting, that I did better by firing single shot and 'walk' the rounds to my target from my hip, rather than put it on full automatic and let the burst go - who knew where.

That Thompson Sub Machine gun, the famous 'Chicago Typwriter' of the Capone gang, saved my life once more in my time in Korea. On Hill 339. Both my leader's hands could still be free holding a radio and map while I moved with my assaulting platoon in attacks. Yet I could reach down and fire instantly from my hip when I needed to.

I thought back to Lt Shanks and his non-standard Springfield rifle.

I simply continued the US Army tradition of soldiers adapting to their tools of their trade in war when the differences between killing or being killed were often when an adaptation worked or not.

Corporal Stephanak the Runner

One other thing happened I sadly remember on Hill 578.

I had gotten pretty well known by my Jail Bird Platoon members by Hill 578. After my taking the top of the machine gun nest by myself their respect for me went up. We joshed and joked at times. I was still an 'officer' and not their buddy. We talked about physical conditioning and I remarked I was a pretty good 440 runner when at West Point. Stephanak challenged me to a race.

About 6 of us guys raced, about 100 yards. The only soldier who could beat me was Stephanak.

Corporal Stephanak was killed in action that Feb 14th, 1951

- Details

- Written by dave

- Category: Korean War

- Hits: 3614

The Short Patrol Where I Lost My Hearing

It was a short patrol - as Patrols Go. Less than a day, but calculated to pin down just where the Chinese were on those hill masses north of Hill 578, which we would have to tackle sooner or later.

I was given a section of 2 M4 Sherman Tanks from the 70th Tank Battalion to accompany me, to help develop where the enemy was. One thing I could use them for, was to supress long range machine gun fire from the higher hills. I was getting accustomed to being shot at from a distance in ways we could not effectively counter - unless we directly attacked their positions. Using the 76mm Tank Cannon might do the trick.

So we clanked along on the lower ground past the main hill mass until we turned the corner and started moving east toward an extension of the hills to the north.

Suddenly we started getting machine gun fire from the low ridge in front of us. I could tell from the crack-thump sounds the machine gun was pretty far away - perhaps 500 yards. I could not see their position! We were exposed, pretty much in the open. We had to silence that thing before we got casualties!

And just then the lead tank pulled up a few yards, its front toward the same hill that the fire was coming from, but it closed all its hatches! I couldn't talk to it on my radio because the Tankers were on different - from our Infantry - frequencies!

So I ran around the back of the tank where the external phone was supposed to be. It was gone! The only thing in the telephone box were two wires that had been attached to a phone. I'll bet - and I saw this before - some Infantry Grunt had run up to the back of the tank when its motor was running, tried to talk to the men inside just as they decided to move! And that caused the phone to be yanked loose as the grunt was probably turned away from the roaring sound of the engines, never saw the movement of the tank - and the phone was yanked out. Damn..

Tankers are in Tanks so they are not exposed to small arms fire. But it doesn't help when they can't see or hear where the enemy shooting at them are, so they can shoot back!

I could hear the machine gun bullets plink off the tank hull during every other burst of fire. Another reason the tankers wouId not open the hatch! I stood where I could brace my binoculars and looked to where the fire was coming from. I saw some smoke after a burst - so I had the machine gun's location pinpointed. Sooner or later I would get a man wounded even though all of them were flat on the ground and in depressions in the ground.

We had to kill that weapon!

So I ran around in front of the tank where the driver and gunner could see me through their periscopes, my back to the machine gun and pointed at the area where the machine gun was located. The gunner rotated his canon in that general direction, but not, as I estimate where it was pointed, not close enough. So then I used hand signals, winding my arms to get him to wind the canon. Finally it was as close as I could tell, and then pointed at his periscope and banged my fists, which meant 'fire.'

The damned gunner and driver NODDED their periscopes with a 'Yes' motion. Before I could get away from the side of the canon, they fired..

The flash deflector sent the shock waves sideways right onto my right ear. It blew out my ear drum, and I have been deaf in that ear ever since!

I've never forgiven tankers for 'nodding' their periscopes instead of cracking open theur hatches. And cursed tank designers for not installing external telephones that can't be yanked out of the tank frame. And I cursed the Army for not getting tankers and the Infantry overlapping radio frequencies!

The one round that was fired seemed to silence, or scare the Chinese machine gun crew. So we patrolled on and returned to report what we had seen. My head ringing for days.

Footnote: I did not seek, nor get, a 3d Purple Heart for my damaged hearing, even though it was caused by 'friendly fire' - which qualified for one for it occured during combat operations. But decades later my family, noting my declining hearing abilities insisted that I apply, under Veteran's Administration rules for a 'Disability' benefit. Before the bureaucracy, and tests, were done, I was ruled that I had 70% hearing loss. So in 2015 I began to be paid $3,253 a month for my Veterans Disability, and was provided a modern-technology hearing aid.

Page 2 of 3