- Details

- Written by dave

- Category: Korean War

- Hits: 3704

Again from Korea. Again from a mountain top.

Yesterday I took out a patrol. It was Sunday ... a Sunday with-

out services ... a Sunday out in that troubled land that lies be

tween two armies. There is no room for a church on our misty

hill in this lonely land of many battles.

No, the day seemed only like a wet, slick day anywhere, and

I wondered, as we moved down the slopes to seek out our en

emies, why the feeling of Sunday had so completely deserted

me. But the ridges, and the woods, and brush, soon pulled our

bodies into a shallow sort of fatigue, and thinking became tire

some. We wandered far, under the fitful skies.

Then, a group of Chinese who had been waiting, opened up

and shot our lead man ... and we suddenly became involved in a

short, sharp struggle of grenades and bullets. But we, at a dis

advantage, had to pull back without our dead soldier.

Yet we knew what we had to do, and soon we set out again to

risk much to get to him. This time we moved - not to gain

knowledge, for we knew about our foe - not for ground, for we

were turning back - not for glory, for we had been there a long,

long time. We returned into a holocaust of bullets to recover

the symbol of someone who had been so alive a short while

before - and we returned in the hope that we, too, would be

treated in the same way, were we ever there.

We set out, taut in every nerve, moving in a high-tension

sort of way. I happened to look at the wet, bony wrist of some

one beside me. He gripped his rifle with a chalky hand. Flesh

and caution, against the savagery of bullets and sharp little frag

ments ....

We set out...an intense group of men ... under that terrible,

broken sound of artillery, and the snicker of machine guns in

the bushes. Then, in a final, fearful second of confusion - in a

second of awful silence, one gutty private crawled up, and with

the last ounce of his courage, pulled our soldier back to us.

We had succeeded. We started back, rubbery legged and very

tired ... feeling a little better, a little more certain there would be

a tomorrow. We had done something important. We were bring

ing our soldier with us.

Then it was night, and the rain was soft again. We drew up

on a nameless ridge and dug into the black earth to wait for the

enemy, or for the dawn. The fog moved in among the trees. I

sat for a long time looking at the end of the world out there to

the north.

Nine months in a muddy, forgotten war where men still come

forth in a blaze of courage. Where men still go out on patrol,

limping from old patrols and old wars. Weary, jagged war where

men go up the same hill twice, three times, four times, no less

scared, no less immune but much older and much more tired. A

raggedy war of worn hopes of rotation, and bright faces of green

youngsters in new boots. A soldier's war of worthy men - of

patient men - of grim men - of dignified men.

A sergeant sat beside me. For him, twelve months in the same

company, in the same platoon, meeting the same life and death

each day. Rest? Five days, he said, in Japan, three days in Seoul...

and three hundred and fifty-seven days on this ridge! Now he sat

looking, as I was, at the same end of the world to the north.

Nine months, and I am a Company Commander now, with

the frowning weight of many men and many battles to carry. A

different, older feeling than of a platoon leader. New men ...I

must calm them, teach them, fight them, send them home whole

and proud ... or broken and quiet. But get them home. Then

wait for new replacements so the gap can be filled here, that

gun can be operated over there.

There is much work to be done. I must put this man where he

belongs, and I must send many men where no man belongs. I

must work harder and laugh merrier... and answer that mother's

letter to tell her of her lost son. Yes, I was there .... I heard him

speak .... I saw him die. So, in many ways, I must write the

epitaph to many families.

There is always that decision to make as to whether a man is

malingering or sick ... whether to send him out for his own sake,

and for another's protection, or return him for a necessary rest.

And one must never be wrong.

One must be ready and willing, always, to give his life for

the least of his men. Perhaps that is the most worthwhile part of

all this ... the tangible sacrifice that an infantryman, a soldier,

can understand.

I see these things still I am slave

When banners flaunt and bugles blow

Content to fill a soldier's grave

For reasons I shall never know

Now it is raining again. The scrawny tents on the line are dark

and wet, and the enemy is restlessly probing. It will not be a

quiet night.

Lt. David Hughes

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

My mother showed that letter above to the Rocky Mountain News, which printed almost all of it.

My mother got several handwritten letters about that letter and what it told them about that endless war.

- Details

- Written by dave

- Category: Korean War

- Hits: 3990

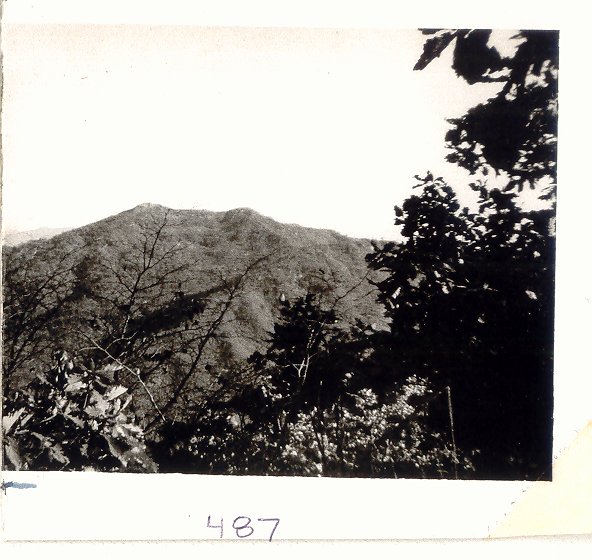

The Bad Hill 487 Operation

Up until August almost all the Plans and Operations of the 7th Cavalry were done with excellent results, including low number of casualties.

For a time, the 3d Battalion occupied Line Wyoming, strengthing it in the event of a general Communist Offensive. At the same time, the fledgling 'Truce Talks' at Panjumon started, and then faltered. In fact the new 8th Army commander, General Van Fleet was sure it was going to take a punishing push against the current Chinese lines east of the Imjim River to get the North Korean's back to the negotiating table.

So he planned a push to a new line Jamestown, northwest of Yonchon, that would be across, but still close to, the original 38th Parallel. That push seemed to be started against a Hill 487. The 2d Battalion of the 7th Cavalry was the first unit to be given the mission.

That hill was not only very steep, but the closer one looked at the top, it became a hand over hand climbing problem. There were large rocks and boulders on top that gave the defenders protection from small arms fire.

Whether it was bad planning, or simply a much harder defense, together with less combat experienced - after the wave of summer rotation - soldiers and officers, they were repulsed. Several times.

Then it became the 3d Battalions time, and my Company K had to commit two platoons. It looked hopeless from the beginning to me. Hill 487 was absolutely dominant, and even plunging machine gun fire down from the top was deadly for the men trying to climb the mountain from the east side.

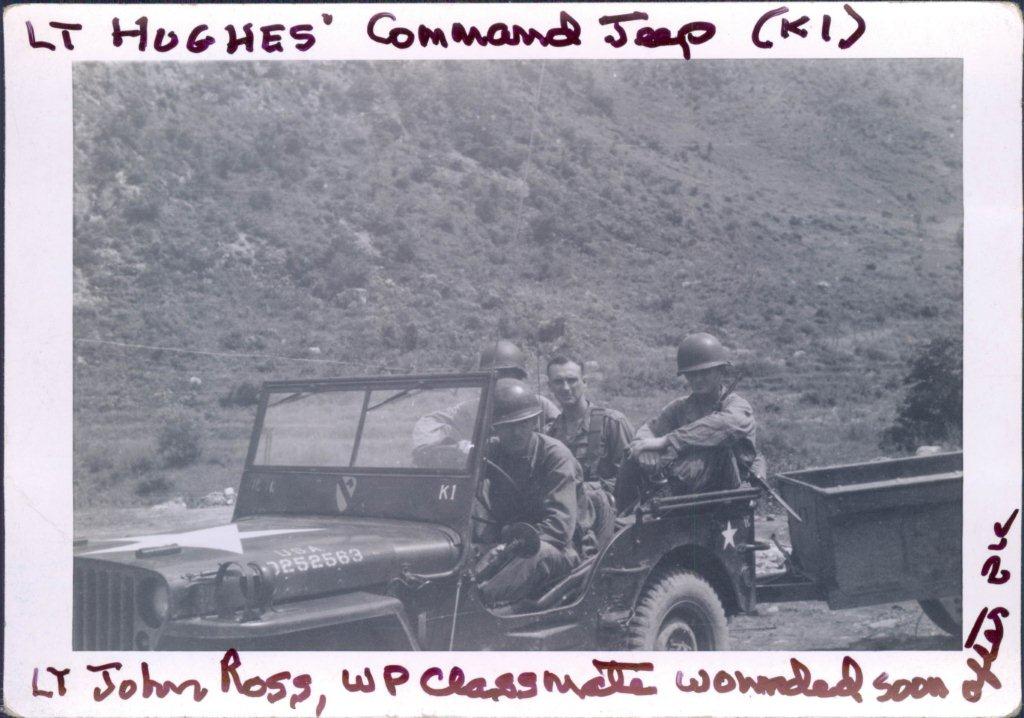

The worst happened. Not only were we repulsed but Lt Ross, the new platoon leader in my Company K, my West Point classmate, was shot up in his right arm so bad he had to be evacuated.

The Battalion called off the assault, and we were returned to the Wyoming line for the entire operation to be reorganized.

It took another Division almost another month before 487was taken. and only after other supporting, Chinese occupied hills fell.

Meanwhile the 7th Cav was having its own problems, in which I seem to have figured prominently, to bring off success. They were called Hills 339, and 347.

- Details

- Written by dave

- Category: Korean War

- Hits: 5494

My Korean War Tour Ends in Japan

When I came off Hill 347 with 192 Chinese Prisoners of War the evening of October 7th, I knew that my Company Command Tour would be over soon. Because of the losses from casualties the last 15 days - all my officers dead or wounded, and 169 enlisted men dead or wounded - leaving Company K with only 15 effective men left, I knew that my beloved soldier unit of Company K was no more. It would have to be filled up with replacements. They had been asked to do the impossible - defeat two full strength Chinese Army Battalions, one in defense of Hill 339, and one in taking Hill 347 - and they did.

Custer would have been proud. I call the battle for Hill 347, Custer's Revenge. I know Col Gilmer was - I lived up to his very high expectations of me as a West Point graduate.

My only regret was that he chose, instead of submitting Company K for an Presidential UNIT Citation, he recommended that I, personally, receive a Silver Star for Hill 339, and a Distinguished Service Cross for Hill 347. I would have traded both for recognition for my Cav Troopers by a Presidential Unit Citation rather than individual awards to me, on their behalf. They, not I alone, did the job.

So my dream when I chose straight Infantry coming out of West Point, a year and a half earlier, was fulfilled. Those American soldiers, over half being drafted, not volunteers, and none being elite Rangers or Airborne qualified performed exactly the way I thought they could right out of Middle America - with the right kind of leadership, organization, weaponry, and training - even if much of that took place during combat itself.

My learning curve was quite steep in the absence of formal Infantry Officer training which was supposed to happen to all my classmates before the war started, but because of the North Korean aggressive invasion, that didn’t happen. And 40 of my CLassmates were killed in the Korean War. So my learning curve had to be greatly accelerated by Captain Flynn, the other 1st Lieutenant officers of Company K and NCO's starting with steady Msgts Ingram, and Abaticio. And of course I would not have had the clarity of purpose, determination, superior physical fitness, and sustained mission focus, without my four apprentice years at West Point, regardless of my academic class standing, and spotty disciplinary record.

Staff Appointment

So it was no surprise to be ordered by Colonel Gilmer to be appointed the Assistant S-3 - operations officer - at the 7th Cavalry Regimental Headquarters. Two levels above my Company position, even though I was still just a first lieutenant. I guess you have to grow into the jobs you are handed by the Army.

There was good reason for that secondary staff position to be filled. For the entire 1st Cavalry Division - all three of its Regiments - 5th, 7th, and 8th - were to depart Korea by the end of December after the fighting died down once 8th Army had shoved the Chinese Armies back over the 38th Parallel and inflicted a large number of casualties on them. It was then time to go back to Japan, back into the same locations in Japan they left from a year earlier. They were to be replaced pn the front in Korea by Regiments of the 45th Division - Oklahoma National Guardsmen who had been called to active duty when the war started, and who had occupied and trained - in the posts that the 7th Cav had previously occupied. (It was a Sergeant in the 45th Division which replaced the 7th Cav on Hill 347 who took the two pictures of the Hill and Trenches in April 1952)

I was to be on the 'Advance Party' of the 7th Cav, and travel to Japan, to make the changeover run smoothly. So I only spent two weeks at the 7th Cav headquarters in Korea near Uijongbu, before heading for Camp Crawford, Japan.

That duty was much less pressure-filled than I had as a Company Commander during those extreme combat operations. I could decompress. I would also have some time to do two things - first to compose and deliver recommendations and sworn statements in support of a large number - over 20 – of my personal recommendations for Combat Awards - from Bronze Stars with V/Device, and Silver Stars, to Distinguished Service Crosses - both for the living and dead Company K troopers who fought with me, and I witnessed, their extremely brave acts during those last 15 days. Secondly, with access to the Regimental operational records, I could learn just how Company K's operations fit into the bigger Regimental scheme during the same time.

I had an intimate knowledge of what went on in my Company K, but I only had a general idea of how the rest of the 3d Battalion, the other three Battalions including the Greeks, and the Regiment and Division as a whole fared during those intense combat periods.

What I learned from that study of records during December and January at Camp Crawford, permitted me to write the 8 page report while I was on the boat coming back to the to the United States in my normal 'rotation' tour. I would send it to Major Flynn then recovering from his wounds at Fort Benning, Georgia. He had written twice to ask me what happed to 'his' Company and Regiment after he was gone. I had no chance to answer him during operations.

My ability to write clearly appears not to have diminished during my year in Korea. While I wrote that letter to Major Flynn, just for his use, mailing it from the port of Seattle on the 3d of March, 1952, he returned the original to me decades later, but also had taken the liberty of circulating it in the 1960s and 70s to people he thought could better understand what American soldiers went though in that 'Forgotten War."

To my complete surprise, that letter was included in 2002 in the book "The 50 Greatest Letters from America's Wars" by David Lowenherz. It shared impressive neighbors - letters from Abraham Lincoln, Gen George Washington, John Kennedy, and General Dwight Eisenhower.

That letter is included here after these first 27 chapters in this biography of the Korean War. It is in 'Korean War (28)'

'Korean War (27)' the next item after this one is called 'The Fickle Gods of War' about all the recommendations I made that were destroyed in a fire after I left Japan.

Christmas on Hokkaido

The three months I spent at Camp Crawford on Hokkaido was a welcome respite from the stressful year from landing at Inchon through the fights on Hills 339 and 347.

Besides the staff job of helping make the incoming Cav, and outgoing Guard process - which took over a month - go smoothly, and my writing down recommendations for awards, I was given one other important mission to carry out before I departed for the states.

Hokkaido is the most northern Japanese Island. And it is very close to Soviet Territory including Sakhalin Island. With the Korean War going on, with Soviet support for the North Koreans, there was US Government nervousness about any activities that the Soviets might undertake, from illicit entry into Hokkaido from the very furthest and isolated tip of the island to intelligence gathering about US units. It would be the responsibility of the 1st Cavalry Division, as an occupying authority on Hokkaido to make contingency plans for any eventuality.

What was needed was a physical reconnaissance of the north western shoreline to the tip of Hokkaido opposite Sakhalin. Also to provide an opportunity, with armed protection for US Army intelligence personnel from the CID to visit the small fishing village at that extreme tip. If anybody knew what the Russians were up to, Japanese villagers and local officials would.

The practical problem was that there is no simple road to drive to that location, no airstrip, and only the sea - in the snowy dead of winter.

I was tabbed to make that reconnaissance in the December winter, using 7 full tracked, three person Army M29 Weasels which could navigate over the snow. They were developed by the Army for operations in Alaska in WWII.

|

|

| Tracked Arctic M29 "Weasel" |

It was also desirable that the 160 mile trek from Sapporo to the village of Wakkanai be taken right along the seacoast to be able to spot anything unusual. There was a reputed horse or animal cart trail that followed the contours of the coast, not at shore level - for there was no shoreline, but up from 25 to 100 feet above the water line,

Of course that trail would be under several feet of snow. It would be quite a navigational challenge. But then if I had handled North Korea roads in the winter, somebody was sure I could deal with snowy coastal Japan.

So we did. 21 Persons, 18 were Army soldiers - drivers, mechanics, radio men, and 3 NCOs with me as the only officer. And 3 civilian American CID men who knew the language. All in 7 Weasels.

Everything went ok the morning we left until one Weasel broke through the snow crust around a turn at least 30 miles deep into the trip and along the coastline with its deep ravines. The driver cut a corner too sharply where the roadway was invisible under the snow. The Weasel fell through and then bounced nose down at least 75 feet in a gully. Simple matter of manhandling it around, pointed uphill, and let it crawl its way back to the trail. Right? Wrong. The engine would not start being flooded with oil.

So it was time for me to use my ingenuity. After several suggestions were made to me, I came up with a solution that would place one Weasel on the trail but where it could crawl down one gully, while it pulled on the dead weight of the other weasel by cable up to the roadway. Then turn around the weasel now at the bottom whose engine could run, and let it climb up using its winch as an assist.

That worked. Within 45 minutes the mechanic got the dead weasel running again.

Geisha and Teriyaki

We got to the village of Wakkanai late in the afternoon. They knew we were coming. And so besides having rooms to sleep in, they got a modest feast up, with a dish I had never tasted before - Teriyaki! And oh yeah. Fish. After all this was an isolated fishing village which probably was as little affected by the war with America as any remote spot in Japan.

And they had their own version of three Geisha girls to entertain us while we ate and drank a rice wine.

We turned in, tired from the day's exertions. If the Geisha girls offered themselves to any of my men, I was not aware of it.

The CID men gathered the information they were seeking, and we set off the next day about noon for the uneventful trip back to Camp Crawford. Mission accomplished. Lesson learned? Teriyaki tastes good. And the Russians had not landed.

Homeward Bound

After lots of Christmas Holiday cheer, with plenty of pretty Japanese ladies around, a well-stocked Commissary to browse for the cash flush war-weary returnees, many of whom were due to rotate, while those who only got to Korea in the last 6 months would stay in Japan with the Cav until their normal – longer than a year – rotation.

News About the West Point I Left Behind

I packed to go home, just as I learned, for the first time, about the first ever major cheating scandal within the Army football team at West Point that had taken place the year - 1951 - after I graduated and was in combat.

Years later in the 1990s - Bill McWilliams, Class of '55 researched, wrote and published a book "Return to Glory" about the Cheating Scandal and how West Point and the Corps of Cadets recovered from its stain. As he researched it he wanted to juxtapose the scandal with exactly what West Point was for - honorably leading Americans in war. So he researched prior West Point Classes, including our Class of 1950 which was immediately plunged into the Korean War - suffering more killed in action than any Class serving in that war. He ran across something I wrote and was published, and the fact that I was the most highly combat decorated member of the legendary Class of '50. I had been doing what West Point was created for.

So he made me the 'poster boy' for his book. Interviewing me extensively, reading what I had written in 1950 and 1951, including my 8 page description of the battles for Hills 339 and 347, and reading the sworn statements my soldiers made that supported awards made to me for my actions in Korea.

When published in 2000, and serialized in the West Point graduate magazine, that, more than anything I can think of, led to my being nominated in 2001 and then in 2004 selected and honored as a 'Distinguished West Point Graduate' - only the 9th Colonel ever to receive that honor which generally was given to retired very senior West Point graduates as general officers. Ironic. As of 2014 I am still the only living West Point Graduate who has received that high honor out of the more than 1,000 retired graduates who live in Colorado.

I had come a long way from being confined to my room in 1950 for cadet violation of rules, and graduating without academic distinction, to become highly decorated and successful in combat in an American war, to being honored for my entire life of service.

But whatever I am credited for in my military service, it is West Point that gets the credit for not only educating and inspiring me to do my sworn 'Duty, Honor, Country' but to take a chance on me at Graduation.

On February 7th, 1952 we sailed on the Oturu Maru for Seattle. The boat was full of Korean War returnees who had been in one regiment or another of the 1st Cavalry Division - the 7th, 5th , or 8th.

While we all swapped war stories the first days and nights out, I went looking for, and found one of the few upright Typewriters on board. So I spent time slowly thinking about and then typing out the 8 page letter to John Flynn about what had happened to 'his company K' after he left, wounded. And I wrote some other letters to distant members of my family. They were all relieved I survived that bloody war in which 34,000 Americans were killed and 8,000 are still missing in action. And that my West Point class suffered 40 killed in action.

It took us, as I recall, a whole 15 days on that boat to reach Seattle, where we were in-processed at Fort Lewis. My orders were to report to Fort Benning, Georgia

Then I was on my way home to Denver for a month and then Fort Benning.

With that, my experience in the Korean War was over.

The Full Text of the Letter I wrote, and mailed, to Flynn is at Korean War (28), two items after this one. The next item - Korean War (27) is about the 'Fickle Gods of War' where 22 of my soldiers were denied recognition because of that accidental fire in Japan. Incidentally, I learned, over a year later, that when the 7th Cav Headquarters burned down the only thing saved were the US and 7th Cav Colors, when the Sergeant Major rushed into the burning building to save them. The honorable tradition of Army selfless service continues on, regardless of rank or position or wars.

POSTSCRIPT -The portion describing our defense of Hill 339 has been reproduced and included in the 2002 Book by David Lowenherz, "The 50 Greatest Letters From America's Wars." Crown Publishers

- Details

- Written by dave

- Category: Korean War

- Hits: 3948

My Maximum Defense Test - Hill 339

Hill 339 became the biggest test for me, and my Company K, 7th Cavalry.

First of all that isolated round top hill, far out in front of the 3d Battalion lines, and very close to the Chinese forces east of the Imjim River in their main defensive line was like a thumb in the Chinese eye. They did not want it occupied by US Forces. I later saw why.

First of all, G Company from the 2d Battalion, 7th Cavalry was first unit ordered up there to establish a company sized Patrol base in order to send patrols deeper into enemy territory and at the same time keep the patrols within range of supporting weapons.

From the first day it was clear the Chinese didn't want that thumb so deep in their eye. They started firing on it with their indirect weapons that they had, at last, been able to bring down the peninsula from China, dig in, and employ.

Company C, from the 1st Battalion relieved Company G on the 5th of September on Hill 339.

At 2200 the night of the 6th, Company C was attacked by a superior sized force. Company C was overrun, suffered heavy losses in both men and equipment. The company completely disintegrated. A heavily reinforced company from the 2d Battalion jumped off from Hills 321 and 343 to recapture Hill 339. Which it managed to do again on the 7th.

They had to carry down the many US soldier's dead bodies from the area aroun the peak of the hill.

It was becoming clear that the Chinese were not going to let the Americans close to their lines without a fight. And that 339 was a bloody piece of real estate.

Why Me?

Col Gilmer, the 7th Cavalry commander got into the act. First he ordered the 3d Battalion to prepare plans for a battalion sized patrol base well out in front of Wyoming, in which one company would occupy and defend Hill 339.

And he directly ordered Lt Col Haldane, 3d Battalion Commander, to put Company K and its Dave Hughes Commander on, and defend, Hill 339. So Col Gilmer apparently thought I was one subordinate commander he could rely on to win important battles.

In an 8 page letter I wrote to my old Company Commander, John Flynn, after he got back to the US, and as I was on the way home in February, 1952 after having been Gilmer's Operations Officer, but was wounded by a mortar attack, I spelled out that battle of 339, and the worst battle to seize Hill 347. You can read that letter. I won't repeat it all here, just the high points.

When I went up Hill 339 - it was uncontested that day, September 21st. The Chinese chose to stay off that magnet for US heavy artillery and mortar fire, and attack at night, as they did Company C, destroying it.

I went up there with my present Company K strength of 6 other officers, 5 on the hill, and 169 enlisted men, and a squad of 10 South Korean Soldiers, called Katusas - from the shattered remains of the Korean Army from the earlier battles. They were to augment US combat units.

The hill was very steep all around. Here is a glimpse of one view.

The other two Rifle Companies I and L completed the perimiter of the Battalion Fire Base. 339 remained, however, the key. Who held that hill dominated all the rest. You can see the entire layout here. "MLR" shows the trace of the Chinese Front Line.

I quickly saw why the Chinese were so determined to get us and keep us off that hill. For not only was it close to their main line defenses, we could see down into the rear of their support areas - and direct artillery, heavy mortar, and air strikes on them.

Immediately we started getting what we would be subjected to for the next 7 days and nights - incessant 81 and 120mm mortar fire aimed right at the peak. We began to take casualties right away.

By 2200 hours that first night we had the first assaults from both the left flank, the right flank of the L-shaped mountain with apex at the peak, and down the north slopes to the road on which we had a 70th Armor M4 Tank and a few men around it, that broke up their first attack there.

Starting the next morning I had ordered more barbed wire, napalm for our two flame throwers, three more heavy machine guns brought up. And lots of ammunition. The Koreans were very helpful at that, since they are used to carrying huge loads. (But I kept them away, at night, from our front line - I did NOT want any of them walking around our foxholes at night - with almost no command of English, with oriental faces, and off color uniforms.

I placed one of the water cooled .30 caliber machine guns right on top of my command bunker, just down off the highest peak. If that had to be used it would be my last line of defense.

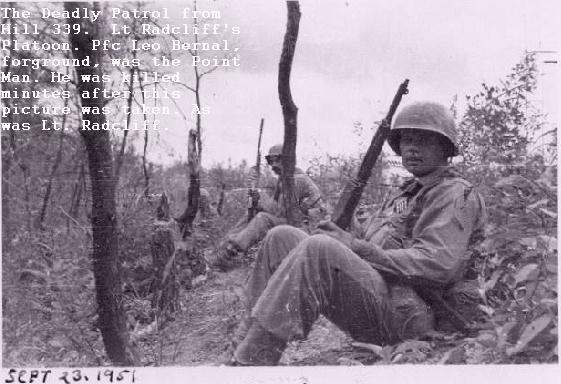

I was ordered then to send out a patrol on the 23d to determine just where the closest enemy lines were. I did not like it, for I could see where those lines were, and a patrol, with little maneuver room, was bound to be the focus of lots of fire from dug in Chinese soldiers.

But orders were orders. And I sent the most experienced officer I had, Lt Radcliffe to lead his platoon on that patrol.

He only got a few hundred yards when automatic fire rained down on his platoon. Radcliff was killed immediately, .....

A Sergeant who was in the rear of the platoon, took this picture of PFC Bernal just minutes before he to was killed on that patrol.

This cat and mouse game went on for 5 more days and nights. The night of the 27/28 was the climatic battle I had prepared my men and unit for. We had already suffered 39 killed or wounded from the bombardment alone over the seven days and nights leading up to their great push.

The Chinese attacked my reduced strength (less than 125 men on the hill itself) company to seize Hill 339, with a 600 man, 5 rifle company, Battalion coming at us after a huge mortar preparation at midnight. primarily over what the diagram shows as the Left Entry Ridge, and the Right Entry Ridge.

The next pages will show how the attack developed all night long.

- Details

- Written by dave

- Category: Korean War

- Hits: 4515

To get an idea what we were up against in the Yonchon Sector from August to November 1951, this map shows that the Chinese had two ARMIES (xxxx), the 63d and 65th opposite the 1st Cavalry Division (xx) and the British 29th Brigade (xx) and the ROK 1st Division (xx)

Below are verbatim extracts of a long 8 page Letter about my Battle for Hill 339 the 21st to 28th September 1951. I hunt and pecked out a letter on the only typewriter on board the Oturu Maro troop ship enroute to Seattle from Japan in February 1952. It was addressed to Capt John Flynn. Flynn had been my first K Company commander in Korea in 1950. He was promoted to Major and was the Operations Officer for the 7th Cavalry Regiment under Col Gilmer when he was wounded by mortar fire while standing next to Gilmer, and then was stationed at Fort Benning as he recovered from his wounds. I had succeeded him as K Company Commander in August of 51.

Since I was sent later on the advanced party to Japan with the S-3 Headquarters of the 7th Cav in December and January 1952 while it was being exchanged with a regiment from the Oklahoma National Guard 45th Division, I had both the time and opportunity to study the classified and unclassified written Cav reports on the operations of the whole 7th Cav, and my 3d Battalion from September through November in the Yonchon sector. Including the battles for Hills 487, 339, and 347, and put them together with my very fresh memory of all three battles. So my extracts below are an accurate description of those operations and their outcomes. Later while at Fort Benning, I prepared an article about the Battle for Hill 339, and the three illustrations below are from that article. They give a visual picture of the text from the letter about the unfolding battle the night of 27-28 September

Before going up on Hill 339 I had learned that Col Gilmer, 7th Cav Regimental Commander had directly ordered Lt Col Haldane the 3d Battalion Commander to put "Lt Dave Hughes and his Company K" on Hill 339 to defend it. Gilmer expected me, a fellow West Pointer who had gotten a reputation for fighting effectively in combat actions over the past several months, to walk on water. This turned out to be one of the toughest combat missions I ever was given.

Start of verbatim extracts from letter to Flynn about Hill 339.

“ Company K got the delightful mission of holding 339, and 1,000 more yards of perimeter.

We moved out and after plastering the hill from an OP [observation post] on 321, 1,500 yards away, we went up, but the Chinese set off a red flare and pulled off. I topped the peak and about five minutes afterward learned what the score was going to be for the next two weeks. They suddenly began shelling us and mortaring until I thought the roof was going to come off the hill.

They kept working the front slope over with a battery of 75mms and self-propelled artillery and they shook us to pieces with more 120mm mortars than I thought we had in 4.2-inch. The rain of 82mm and 60mm was just incidental. The fewest incoming rounds we ever reported for 24 hours was 350, and we estimated 1,200 on the second day.

It took me until the second day to see why they had targeted us while hardly touching the rest of the perimeter. Once on the peak OP, I could see more of their positions and gun positions and access routes than they could afford to have me see, or order my Artillery and Mortar Field Observers to command long range fire to come down on them.

So it went. We dug in amidst dead enemy troops from earlier battles and tried to organize the hill. They watched us like hawks, though, and could see our rear slope from the flanks. We could not top the ridge or put a single man in position on the forward slope during daylight; they would just open up with the SP [self-propelled] guns and dig him right out of the hole. From bombardment alone, with very little movement on the hill, we took 33 casualties in a week from direct hits on holes with mortars and the midnight dose of 120's.

The first night, we had a scrap. They came across a little saddle from which they had hit Company C, and they came down the road on the extreme right flank. On the road they ran into a tank, and it scattered them while the mortar fire kept them dispersed. But on the peak they plastered us with everything they could, and came in right under their own mortar fire to hit the right shoulder of the hill and smack into Sergeant Malloy's machine gun. He waited until they were ten yards away and then cut loose. They did not definitely locate him in the confusion and noise, and he stopped them cold. They crawled around and poured machinegun fire on us for a few more hours and then pulled off their dead and withdrew. In the morning there were five dead enemy within those ten yards of Malloy, and one had his hand draped over the parapet. We took no casualties from the small arms.

This cat and mouse game went on for seven days while we took the brunt of all the fire in the battalion.

I made out a little card on the company positions and numbered the draws and worked the 60mm gun crews until they could get a round off on any concentration in 30 seconds. We were all up on the peak. It was only about 1,000 yards across the high ground, and nobody was more than ten yards from the crest, including the mortars. That paid off later too. Black Lieutenant Walker commanded the Weapons Platoon.

We sent out daily patrols that only got 600 yards before getting hit. On the 25th, I had to send out a platoon toward positions I knew were there. I didn't like it at all because the enemy had been get cagier and cagier and had been holding their fire. But out went Lt. Radcliffe and his 1st Platoon. The Chinese let them get 200 yards from the peak before opening up with cross-firing weapons. Radcliffe was killed instantly. The platoon sergeant, a corporal, didn't hesitate. He ordered marching fire , and the platoon took half the peak so the rest could get out. There were three dead. Sergeant Brown was cut down by a grenade near Radcliffe. He rolled over and took Radcliffe's .45 pistol and the maps and took them all back as he himself was carried out. A machine gunner who could not find a vantage point to set up his machinegun went up with it cradled in his arm with one belt of ammunition. He had to be evacuated for the burns on his arm. “

“Every night, enemy patrols would crawl up and feel us out. They plotted our weapons and counted our men. Every night I would have to get up and calm down a squad that thought the whole Chinese Army was out there. But this had one good effect. The men dug in tight. They kept their weapons spotless. They slept in the daytime and watched at night. The 60mm mortar crew got faster and faster under black platoon leader Lieutenant Walker, who had been school-trained in weapons control. I collected heavy machineguns and on the 28th had five heavies and seven lights across the front. But because of the fire and dwindling number of men, we had been able to put out only a few rolls of concertina wire on the two easy approaches. The engineers all but refused to work laying mines in front of us.

The night of the 28th came. The day had been quiet and it seemed as good a time as any for the big show. “

At 2330 a bombardment came in. It was deadly accurate and concentrated on the positions controlling the two approaches. It continued until 2400 and then, for a few minutes, stepped up to a frenzied firing of all kinds of shells.

Then I heard the rip of a burp gun on the left. At the same time, just as I popped out of my bunker, a purple flare went off on both flanks of the peak. I yelled off a series of concentrations to the FO's (forward observers), and the first sergeant roused the 60's on the phone. But before I had even given a command to the 60's, two plop plops came out, and in a second a flare was burning over each flank. They had fired in about 20 seconds from the enemy flares.

“By this time, all the defensive fires were going full blast, but I was waiting for the Sunday punch. It came in about 20 minutes later at 0110. The Chinese only had a strip of our territory about 150 yards long on the right and 200 yards on the left, but they sure filled it up. They moved a mortar onto the ridge of each flank and began peppering the CP (my command post). They got a couple of machineguns up there and fired overhead for their next attack. And they never stopped pounding the top of the hill with those 120s. Then they jumped off again. The Chinese companies that had penetrated sent people around behind us,, and they raked the back slope with small arms and cut off our communciations with battalion.”

I did not know this at the time, but two things had happened. One was that they had attacked neatly, the first time, just to the left of the two machineguns on the right flank and thus never touched any part of the 3d Platoon. Only two rifle platoons, with perhaps 60 men, were involved all night long! The second thing was that at the beginning of the attack, the battalion S-2 (intelligence) section had been monitoring the SCR 300 (captured US radio) stations, and their Chinese interpreter picked up the command channel of the battalion that was attacking my company. So all night long battalion headquarters had a running account of the battle and knew how we stood, from the talk on the company radios the Chinese used and their command radio. But, we on 339 did not know that, for we could barely communicate to battalion heaquarters.

When the big attack came at 0110, the two companies on the ridgeline on both flanks started the attack toward the peak. Just when they were exterting maximum pressue on the heavy machineguns at the shoulder of the peak on each flank, two more companies came at us on those two saddle approaches we had wired in. I was waiting for that, and on the left, as they started across the wire, we opened up with the 57mm (recoiless rifle) at 20 yards on the wire, and I called in the 155s at a range of 150 yards from us and the two fires caught the company on the move. “

On the right they attacked across that little saddle, and we were waiting there too. At the first sign of the attack I called in the 4.2 mortar fire to 125 yards, and it played havoc with the supporting troops. I started the 60mm mortars firing at top speed (by this time we were getting artillery flares) and then, as the first grenade throwing wave hit our positions, we turned on our two flame throwers. The first wave just expired [fried] where it was. In a short time we were out of flame thrower juice, but it had scared them and the next waves walked across instead of running. I kept dropping the 60mm fire closer and closer until we went to 83 degrees - firing nearly vertically - when firing on a gun to target range of 65 yards and we were dropping shells only 15 yards in front of the machinegunner. PFC Mostad went back and forth between the ridge and the guns and actually gave the firing commands directly down to the 60mm mortar gunners by voice. Things were VERY dicey. It finally broke them, but only after they had got the 2d Platoon CP and had the platoon backed up to our mortar position.

On the left they got much closer. They killed the crew of one of our heavy machinegun sections, broke through the refused flank, and came steaming up the hill at our CP about 35 yards up. I had every man I could spare on the perimeter, including the 5th Platoon (South Koreans) which did good work that night, so I asked my personal radio operator, PFC Citino - who had never fired a Heavy Machine gun " to commit my last reserve. That consisted of one heavy machinegun that was sitting on top of my CP bunker. He set it up and stopped the attack 15 yards from the CP, which was full of wounded. Then I sent my first sergeant to the 57mm recoiless rifle section, which was now in an untenable position. As the section soldiers came up the hill a Chinese soldier came up with them, and after a tussle was killed in the CP. [I shot him with my Thompson submachine gun after he jumped into my foxhole hole with me]. “

“That was the high point of the attack. They had captured three of our men on the left. One of them they took off the hill immediately; the second and third were pushed up in front of them toward us during the attack, but one - seeing that heavy machinegun kill all of their mortar crew and cut down on the attack wave - kicked his captor in the balls, jumped over the side of the steep ridge, and escaped. The third GI went on up and was killed by our fire. “

“At about 0330 the artillery was out of flares, we were low on ammunition, even with our stockpile, when a flare ship arrived and helped us see to counterattack the high points of the attack.

The reserve heavy machine gun had done its work, but its water cans were full of holes. Our urine had run out, but a can of cold coffee lasted the rest of the night.

The enemy radios had reported that three of their company commanders had been killed and they could not get the GIs off the hill. They asked permission to withdraw but were told they had to have the hill "tonight." Then the reserve company, the fifth one, claimed they had so many wounded from the artillery that they could not carry them back and therefore could not attack. Of course we didn't know any of this.

Then our Regimental Commander hailed a flight of B-26s, and under flare light and by radar they dive bombed the ridge 600 yards in front of us.

We drew up in a tight perimeter at 0430 and waited out the day. In the morning we cleared the flanks and bombarded many enemy trying to flee over the hills and down the slopes with their wounded and dead.

We still could not move around very well, because the enemy fire was still coming in, but by 0800 we counted 77 Chinese dead within our positions. Regiment reported that the Chinese suffered hundreds more killed and wounded. We had suffered 10 killed, 15 wounded, and 1 captured.

We were pretty beat up by this time, having taken - with attachments - 54 casualties in the seven days on Hill 339. On the 29th, we were rotated around the battalion perimeter and Company I took over Hill 339.”

------------------ end of verbatim extracts of the letter to Capt Flynn ---

Our Company K had just defeated a 600 man, 5 rifle Company, Chinese Infantry Battalion, after a week of intense bombardment, nightly intelligence probing attacks, and the urging of their higher commanders.

Colonel Gilmer got me a 2d Silver Star (1st Oak Leaf Cluster) for this battle and my personal actions. I am not sure why. It was my company that defeated that enemy battalion, not just me. Maybe he learned about my having to personnaly kill the Chinese who reached me.

See '2d Silver Star' at http://www.davehugheslegacy.net/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=225:medals-and-citations-2-dscass&catid=100&Itemid=204

The Pacific Stars and Stripes had a big article on this battle, and reports on it appeared in numerous newspapers across the US.

I was pretty shaky for a couple days after that very tough week. Once Company K was off the 339 peak, Gilmer said he wanted to see me. I went back to his HQ. He congratulated me, but then ordered me to sleep in his trailer overnight. He seemed to sense my shakiness and bone tiredness. And I was emotional about the death and capture of my guys. The one man captured was the only Company K soldier made a prisoner during the whole Korean War.

A year later after I got back to the US, I wrote another story to get this battle out of my system. It was true but not with his real name. "The Death of a Soldier" Again, like Shanks Bootees, it was published nationally. This time in the April, 1953 issue of the Ladies Home Journal. Below as a PDF file you can read it. Click on

Perhaps writing was my therapy for what today would be called PTSD.

But I still had one more huge battle to face.

Page 3 of 3