Long Patrols

Before attacks were launched against the Chinese Army in the western half of Korea, the 1st Cavalry Division sent out a whole series of Patrols over quite a span of time, into April. The Chinese had pulled well back and the 8th Army Intelligence wasn't sure where they were, just what they were up to, or what kind of units were there.

So I was picked to do a long patrol where others had failed to find the enemy.

After it was over I sat down and wrote an account of it to my mother. She passed it on to the Denver newspapers, and they printed large gobs of it.

Here it is, verbatim. I wrote it on April 1st, April Fools Day.

April 1, 1951, Chunchon, Korea.

Dear Mom:

Again from a mountain peak, this time the highest ever, Hill 899, a mountain almost 3,000 feet from valley to peak.

The Marines are to the right of us, and the Chinese are in front of us.

I have a rather interesting story to tell about our last, and

most successful patrol -- a patrol deep into enemy territory.

We had been sitting on a 650 meter peak overlooking Chunchon and the Song-Gang River for several days, while patrols attempted to cross the river to find the exact enemy positions.

But all of the patrols had returned, saying that the river, a swift channel 200 feet across, was unfordable. And that the Chinese had it covered with machine guns.

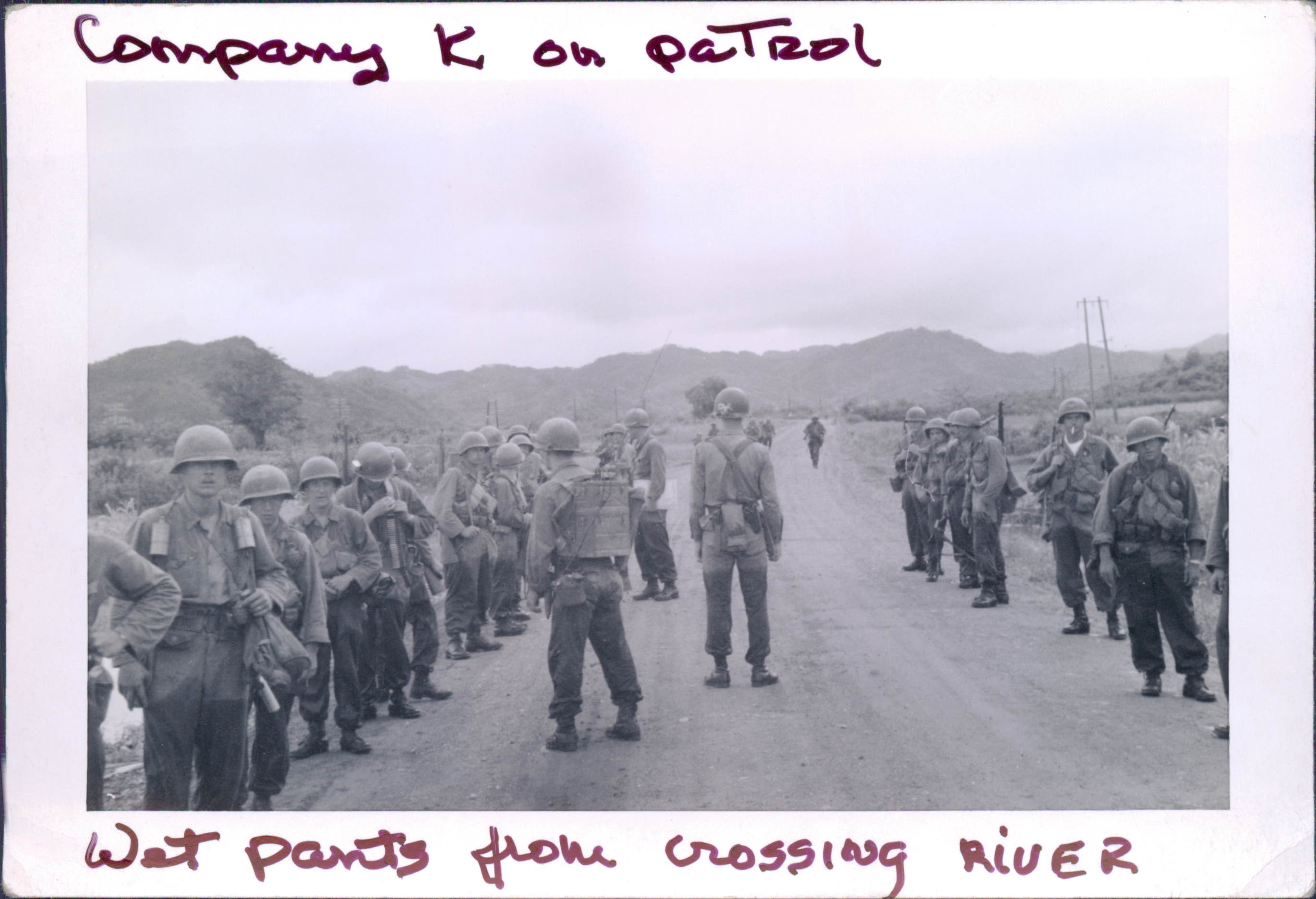

But the information was vital and so they sent us, Company K, saying, "You will cross the river." An order.

We set out, my 50 men and I, with a mortar, a 57 MM recoilless rifle a map and a mission. We started at six o'clock in the morning with the mountain fog so thick that one could not see the length of a squad. Our final objective was a mountain peak six miles away, over four intervening mountains) a gauntlet of enemy top ridge machine guns, a deep valley with a 200-foot river without boats or bridges -- and a record of five other patrol failures to reach that objective.

By ten o'clock our radio reception was too weak to keep us in touch with our friendly lines.

We plugged along through the fog, over ridge after ridge, after ridge, hoping our compass wasn't being affected by the ore in the mountains.

Finally I looked at my map and decided we were on the right peak, and so we began the long descent down a deep slope through jungle- like undergrowth.

But when we reached the bottom and cleared the fog, I realized that the valley went in the wrong direction. Suddenly a South Korean appeared out of nowhere and began jabbering wildly. After listening for a little while to a mixture of Korean and Japanese lingo, we realized he was trying his best to tell us we were very close to two machine guns of the Chinese, and that they had ambushed a previous patrol just two days ago. I saw then that we were one valley short of our route, so -- with a long look at the tiring men behind me, I started up the long, long trail.

By noon the fog had lifted and we were back on the right ridge, ready to drop down again, 1,500 feet to the river below, I ordered a short break, we gulped a C-Ration, and in fifteen minutes were on our way.

We had brief contact with an artillery liaison plane who carefully looked us over beore we convinced him that we were G.l.'s deep in enemy territory.

On the way down the mountainside one man dropped his helmet, and it rolled 1,200 feet before stopping at the river's edge. Well announced to the enemy by the rolling helmet, we reached the water's edge by one o'clock, and after a short search of the area we set up a mortar, cannon and machine gun to cover our crossing, lest some well-placed sniper pick us off in the water, and, with a prickly sensation at the back of my neck, I started wading across the river. The cold water went up, and up, and up. Soon it was up to my chest, and I was unable to move for the current. We just couldn't do it here, so I ordered the platoon back to the shore.' But luckily for us, an old Korean came wobbling down from his wretched house, and without a word, beckoned me to follow him down stream.

He went about 100 yards and then pointed to a lone tree on the other side. I understood; it was an old Korean route across on a hidden sandbar.

We started out again, and this time just as the water reached my neck, I felt the slope go up and I was soon on the other side. The platoon followed, but it was apparent the short men could not make it. So, leaving ten men on the south bank to secure the crossing, we headed north again, dripping wet, and shivering in the bitter wind.

However, one forgets physical discomfort soon when operating in enemy territory, and the late afternoon sun began to quell our trembling after a while.

We had been going for eight hours steady now, and some of the older men, and the "unhardened" replacements were almost exhausted. I urged them on till we turned up the last long valley to our objective. That could really be a trap, so I dropped the tired men here to secure the mouth of the valley, and hurried up the final mountain with the last two squads.

I was reasonably sure there were no Chinese on that particular peak, and after seeing how late it was, I drove up the mountain without caution as the men straggled out behind.

It was then and there I thanked my Colorado mountain Up-bringing and West Point physical training that had prepared me for such a life .

Five of us gained the top by three PM and no enemy was present. There was another peak towering above us, however, that was suspected to be occupied by the enemy, and if our mission were to be entirely successful, we should be able to tell Headquarters if the enemy were there or not.

There was one risky way to find out, so I gathered all of the squads together on the very top of the peak, in an exposed position, and began milling around, preparing a good target.

Sure enough, in a minute we heard a Brr Brr Pop Pop and bullets started whizzing by. We jumped for cover, fired back, and I started to radio back to the company.'

Then we discovered that the radio had shorted out completely in the water and was useless.

I marked the enemy positions on the map, lest I become a casualty, and ordered the withdrawal. It was then I noticed that we were only a few thousand yards from the 38th Parallel.

I then I announced it to the men, one of them fired a round from his rifle in the general direction of the boundary line, and muttered something about l'll get something across that Parallel, anyway!"

We clambered down that mountain as fast as we could, for our mission was not to fight 'em, but to find 'em.

All the way down the mile long valley the Chinese sniped at us but we suffered no casualties and soon got to the river, picking up our outposts as we went.

The return across the river was sure to be more difficult because we had to push upstream against the current.

So three of us, armed with poles, set out dragging a long piece of Chinese communication wire behind us in order to make a sort of guy-line till the last man, Pfc. Gingles, from Abilene, Kansas, lost his footing and started to drag the two of us down stream. He finally got loose from the wire, but weighed down with an 18-pound automatic rifle, and a 15-pound ammunition belt, he began to tumble end over end down-stream.

Then the drag on the line became too much for Pic. Lewis and me and we began to get pulled off the sandbar.

Gingles got free from his equipment and tried to make for the shore, but when he saw Pfc. Lewis slip under the water, he yelled. "Lewis can't swim". and turned boldly back into the stream. I was all fouled up in the wire. and between my steel helmet my heavy boots and clothes. I quickly went under.

In a minute we would be swept into the narrow rocky curve below and into an area where the Chinese had their guns over the river.

Somehow I got loose from the wire and shed my helmet. and after endless swimming and banging along under-the water I reached a shallows, where I stood up to look for Lewis , He had gone under several times and was gasping and gagging, but Gingles had managed to pull him toward the shore, and by this time the men that we had left on the south bank had made a chain out into the water and dragged both of the men to safety.

The three of us lay for a while, utterly exhausted -- Lewis was unconscious the patrol was split -- and we were still five miles from our lines, with the enemy knowing of our presence.

To add to the bad situation, our only map had floated away downstream. It was then four-thirty in the afternoon, and night would soon be upon us. There had to be another decision, and quickly.

I shouted across to my platoon sergeant, Master Sergeant Carl Irvine, of St. Joseph, Missouri, to take his part of the patrol down the north shore about three miles to where another Battalion had made a crossing several days before.

My half of the patrol carried Lewis to a covered draw and we

built a roaring fire, which helped to revive him, and also to take the cramps out of our aching limbs.

As soon as possible we set out for our lines, and I tried hard to remember what the map looked like in this sector.

Just before darkness closed in we reached the top of a commanding ridge, and I glimpsed a familiar looking peak in the distance.

We set out in earnest, tired to the very core, but knowing that our safety lay only in movement.

The other half of the platoon had set out immediately and by dark had surprised an enemy patrol, dispersing them; had contacted a friendly patrol, radioed our predicament back to our lines, and re-crossed the river on an underwater bridge to safety.

We were in trouble though. We slowed to a crawl in pitch darkness as we tried to make our way along the high cliffs and ridges. But about eight o'clock the U. S. Army began to operate to help us on our way back. Knowing it was useless to send out patrols over the vast expanse of mountains, they relied on artillery and searchlights to help.

The first thing we saw was a powerful, wide searchlight beam shoot into the sky over us and light up the whole area, with the glow reflected back to us from the cloud base. Then another beam shot up.

We were able to move faster. Then we heard the ominous whine of an artillery shell speeding toward us.

We jumped for cover, thinking we had been spotted by the Chinese or mistaken to be Chinese by our own units.

But as we waited for the deafening explosion, there was a welcome "POP, and the bright glow of an artillery parachute flare lit up our path. Then we knew we were O. K. -- and with the help of searchlights and flares, crossed the welcome challenge of our company outpost at eleven-thirty P.M., after seven teen and one-half hours of grueling combat patrolling.

I phoned in a complete report to Headquarters, and was told

that we had done an excellent job of getting all the information needed on which to plan future operations.

That was my reward.

The reward for my men came a few minutes later when it was announced that hot coffee and cinnamon rolls had arrived from away back at our field kitchen, where a cook had been "sweating out" our return.

The lusty shouts that went up heralding our return must have

disturbed even the impassive Chinese leering at us from the far off hills to the north.

Love,

Dave