- Details

- Written by dave

- Category: Korean War

- Hits: 7195

ARRIVING IN KOREA

I flew from the United States as a military replacement for the 8th Army, first to Tokyo International airport, then by ship, landing at Inchon, South Korea, in the aftermath of Gen MacArthur’s historically successful Marine Corps landing there to cut off the North Korean Army from its rear. That was followed by the ‘Breakout’ of the Pusan Perimeter in the south by the 8th Army, led by Task Force Lynch – the 3d Battalion, 7th US Cavalry Regiment, which overran trapped North Korean units all the way to Seoul before crossing the 38th Parallel border between North and South and continuing on the historic ‘Invasion Route’ north from Seoul.

I was luckily assigned as a replacement officer to the famed 1st Cavalry Division, which then assigned me to the legendary 7th Cavalry – Custer’s old outfit – and the 7th Cav assigned me further to Company K, 3d Battalion, 7th Cav. Which, interestingly enough was the lead company, commanded by Captain John Flynn in the breakout, with the deepest 24 hour penetration into enemy territory in American military history – 114 miles.

As it turned out I could not have been assigned to a better US Army Division, US Army Regiment, Battalion, and Rifle Company for an inexperienced 2d Lieutenant who never had the chance even to go through the Basic Infantry Officers Course – which was routine for all Infantry-Branch 2d Lieutenants prior to, and after, the Class of ’50 - before I was plunged into combat.

I had to catch up with the Cav Division from Inchon, for the entire 8th Army had pushed north past the 38th parallel border very rapidly after the backbone of the North Korean Army was broken. It was at the Yalu River 200 miles north by the end of November. I had Thanksgiving dinner at a Replacement Company in Pyongyang, the Capital of North Korea which had been overrun by the 1st Cav.

I then caught up with the 7th Cav near Kuna-Ri just as it had stopped, encamped, and been put into 8th Army Reserve for a breather while the 8th and 5th Cav Regiments pushed patrols onto the actual Yalu River’s edge that marked the border between North Korea and China.

My first exposure to the actual fighting soldiers and officers of the 7th Cav came after daylight after we offloaded from a 2 ½ ton truck in the dark and slept in a large windy tent with several other replacement officers. We would be taken to our company units the next day. It was cold, but not severely – yet. I had my issue down-filled sleeping bag which I had been warned not to get wet by the supply sergeant who handed it to me back at the Replacement company in Pyongyang, lest it would lose its ability to retain body warmth.

That was one of the most important pieces of Army equipment ever issued for the Korean War. In fact a retired Infantry Chinese Colonel who fought against our 1st Cavalry Division, said 50 years later to me – translated by my Chinese daughter in law “You had better sleeping bags than we did.” True. For the entire American 8th Army was about to experience one of the severest Korean Peninsula winters on record.

The Garry Owen

While waiting for the administrative staff to take us to our assigned companies that November 26th, 1950, I was able to stand by and watch a pretty large 7th Cav Regimental Review and Awards Ceremony, with a Color Guard out in front of the ranks of the men who were to be decorated. Col Billy Harris, the 7th Cav Regimental Commander drove up in his jeep which had a western horse saddle across the hood. And a big metal 7th Cav emblem on the front bumper. Col Harris, shorter than most of the men, wore a very long insulated and lined overcoat that came all the way down to his boot tops. He wore a Pile Cap with, with his colonel’s rank eagle insignia on its front. He had a cane.

|

|

| Col Billy Harris - note the saddle on the jeep hood |

Colonel William 'Billy' Harris, Commander of the 7th Cav Regiment in Korea

Before he went out to accompany Gen Gay making the awards he held up, for a photographer, a captured Korean or Chinese horn that I learned soon enough, was blown by the enemy during attacks.

The 1st Cav Division Commander Major General G Gay was driven up next, for he would actually pin the awards on the soldier’s uniforms.

This was a rare formal ceremony in the field in the midst of a war, with all who attended armed and in their battle dress. I learned it was the first chance commander Col Billy Harris had to address his troops since the 7th Cav landed in Korea July 22d, four months before, before bitterly defending the Pusan Perimeter, and then attacking north the entire 400 mile length of the Korean Peninsula.

Harris made a stirring speech recounting the accomplishments of the 7th Cav, and paid tribute to those killed in action.

And while the Adjutant read off the citations, General Gay pinned Silver Stars on the field jackets of a number of the troopers, and Bronze Stars with V/Device (for Valor) on others. Then Chaplain Griepp read the 23d Psalm, a bugler sounded Taps, and another chaplain read off the names of the dead soldiers who were receiving posthumous awards for their bravery.

The men were not turned out with polished boots or particularly clean and pressed field jackets or pants – they were combat soldiers right off the line – which they would go back to as soon as the ceremony was over. They had their Steel Helmets on, some had 1st Cavalry patches on their jackets, some were in brown leather combat boots, others wore something strange to me, insulated ‘shoe-pac’ boots.

Watching that ceremony and listening to those citations for combat awards for what those men, living and dead were being cited for, I got an unexpected introduction into the ‘Garry Owen’ – the motto, the song, the name and reputation – most associated with the 7th United States Cavalry. It was not an ‘elite’ unit, and in fact was a boots on the ground, not horse, cavalry unit which it was throughout WWII. But General McArthur chose the 7th Cavalry to parade down Tokyo's main avenue after the Japanese surrender. By the Vietnam War it was 'air'cavalry. But it had pride based on its military history – which is what I knew was a valuable asset for men’s morale in war. It was exactly the kind of unit I wanted to be part of, and if I made it, to command in it at a higher level that Rifle Platoon.

Next Korea(2)

- Details

- Written by dave

- Category: Korean War

- Hits: 5531

Company K

The regimental and battalion staffs were so busy that day of the Regimental Ceremony, they didn’t get around to getting we replacements to our units until after dark and we had eaten the rations they had for us.

The temporary encampment of the 7th Cav near Kuna-Ri was hardly like a stateside Army post. It was all tents from soldier pup-tents to larger ones, trucks small and large. And all three Infantry battalions, the 77th Field Artillery Battalion, and the various headquarters and supply companies were bivouacked in clusters, with a well guarded outer perimeter. About 5,000 men.

The defeated North Korean Army threat was so slight by this time, the Regiment was not even worried about long range Artillery fire hitting their camp. If NK artillery had been a credible threat, no way would the Regiment have had a massed ceremony such as it did. Too tempting a target. But getting administrative 'office work' done was not easy under such cold and remote area conditions.

I vividly remember to this day when Company K’s First Sergeant led me to a small tent in the dark, where he said were Captain Flynn, the company commander and Lt Ryan, the executive officer. When he asked permission to enter, someone said ‘Ok, Sergeant’ and he opened the flap to let me in. I saw a low-light Coleman lantern on a table, two wooden cots, and in them two figures on their backs inside their sleeping bags zipped up to their necks. They could see me standing there in the low light with my helmet on, wearing my Field Jacket with my duffle-bag hanging down from one shoulder and my .30 Caliber Carbine handing from the other.

The First Sergeant said ‘Sir this is Lieutenant Hughes, the replacement officer Battalion said we were going to get.”

Flynn thanked him and said ‘Welcome to Company K, Hughes. So you came from West Point?” He chuckled.

I said ‘Yes sir.’

And both he and the executive officer sort of guffawed, like they were sharing an inside joke. My heart sank. These sounded like they were non graduates who had some kind of ‘attitude’ against West Pointers, especially green lieutenants.

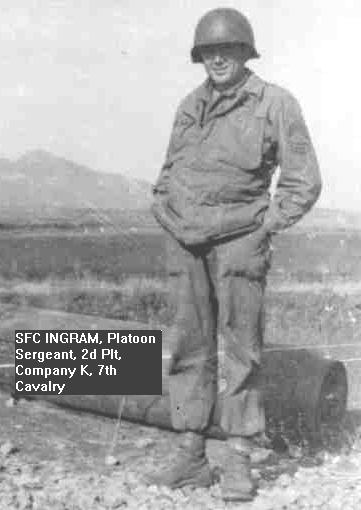

But then Flynn said “That’s alright. We will take all we can get. I am assigning you to the Second Platoon, which has no officer platoon leader, just Sergeant Ingram, a good man.”

And with no more said, and nothing asked of me then, he said “First Sergeant, take Lieutenant Hughes down to the 2d Platoon and turn him over to Sergeant Ingram. I’ll see you in the morning. Goodnight.”

I answered “Yes sir” Saluted in the dark, turned and left with the First Sergeant.

I was at the beginning of my learning curve. I now ‘commanded’ a 40 man platoon of American soldiers.

The 2d Platoon, K Company, 7th Cav

On the short way to where Sgt Ingram's - a Sergeant First Class - SFC - pup tent was, the First Sergeant, who seemed pretty young to me said "Captain Flynn is a great company commander. He has a sense of humor. He is also from West Point."

That gave me a start, but that was settled. Sense of humor in the middle of the war that was never supposed to happen.

SFC Ingram was pretty lanky, seemed older than the First Sergeant. He was 32 and was a career soldier, who had enlisted during WWII.

He jumped up from his tent and saluted me and immediately was concerned for my welfare - like where was I going to sleep. He called out two men from their pup tents and sleeping bags - it was at least 9PM by now. They helped get another tent up for me.

|

|

|

|

| Typical Pup Tent in summer |

I soon was sacked out in my own pup tent, sleeping bag, my dufflebag with the only personal belongings I had with me occupying the other half of the tent. About the only time I would, as an officer, share a pup tent would be with my platoon 'radio operator.' So critical is quick communications in combat, that I would soon have my platoon radio operator shadowing me where ever I went, day or night.

I slept until the noise of men getting up woke me about 5:30 am.

Before I even had a chance to warm up the can of ‘C Rations’ beans and coffee and a tin of fruit salad that constituted my breakfast, I was summoned to Captain Flynn’s ‘CP’ – company command post. Just a space with a wooden table near his tent.

The other three platoon leaders had been called together also. It was the first time I had to see who they were and what they looked like. And to see Captain Flynn and Lt Ryan, the exec, out of their sleeping bags.

Flynn was taller than I expected. From West Point he would have been a cadet in one of the ‘flanker’ companies. And solidly built. He was about 30 years old, it seemed. With a smiling Irish face. I later learned he graduated in the Class of 1944 and saw the tail end of WWII in Europe.

|

|

| Captain John Flynn, CO, Company K West Point Class '44 |

Captain Flynn as he looked as Company K commander during summer on the Pusan Perimeter. Only picture I have of him in Korea.

Lt Ryan’s flaming red hair and sharp tongue was what struck people about him. Maybe in his mid 20s.

The other two Rifle Platoon Leaders were Lt Richard Shanks and Master Sergeant Abaticio. I don’t remember the Weapons Platoon leader, a warrent officer. He made no impression on me even though he was there.

Shanks

The thing that struck me about Shanks from the beginning was that he was carrying a full sized obsolete Springfield Rifle instead of the .30 Caliber smaller Carbine that officer Platoon Leaders like me were issued normally - one of which which I was carrying on my back with the sling over my right shoulder. The 1903 Springfield which he was carrying was a WWI model which was made in quantity in 1944. It was not the same semi-automatic M-1 Garand – which his men were carrying - same model M1 rifle I paraded with at West Point, and fired on the rifle range during Camp Buckner to earn my Expert Rifleman Badge. I wondered why he carried that obsolete, bolt-action rifle.

I learned later three things about Shanks, already a 1st Lieutenant with some prior troop experience. He had come over from being stationed in Okinawa when the 8th Army was still locked into the Pusan Perimeter and short on manpower. He was given the 1st Platoon. He carried that bolt-action rifle for its renowned accuracy and near immunity from cold. It was taken off a dead North Korean soldier. It was his personal preference for his personal weapon.

I was thus introduced for the first time, up close, to the propensity of American soldiers - officers and men - to get their hands on weapons and equipment that they were comfortable with when the time came for deadly combat action. Even if they came from dead enemy troops. They have to be sure they will fire the same ammunition that is in the supply chain, but experienced soldiers want to fight with weapons that they think will protect them best while killing or wounding armed enemy soldiers and defending themselves.

I wondered, uneasily, what did Shanks find wrong with the .30 Caliber Carbine I was carrying and which was issued to him when he got to Korea.

It was no time for me to ask such questions as we gathered around Captain Flynn

I also later learned from Sgt Ingram that Shanks had won a Silver Star for his personal actions around Osan, South Korea, in September, destroying two Russian built T-34 Tanks manned by North Koreans, with just his Rifle Platoon and the newly arrived 3.5mm Rocket Launchers. He was already a seasoned and very respected officer among his men, which is the most important thing that counts in combat.

He also had an easy smile and often whistled happily as he walked.

Abaticio

When I saw MSGT Abaticio he was wearing only his field jacket, with his bare right hand stuffed into its pocket, while others wore pile lined coats, like me, that everyone were being issued in the arriving bitter cold. His left arm carried an M1 rifle with its sling over his shoulder The M1 was what all his soldiers were issued and fought with. He always looked that way when I saw him later, no matter how cold it got. He too had had been in many firefights all the way from the desperate defense days at Pusan to the breakout.. He had a reputation for being a rock of a platoon leader, even though only a Sergeant. Flynn was obviously quite satisfied with him as the 3d Platoon Leader. Abatecio was always serious-faced and kept to himself. His officer platoon leader had been killed during the Pusan Perimiter actions, and was never replaced.

Then Me, Combat Platoon Leader

Then there was me, with new uniforms, a brand new light .30 caliber M-1 Carbine on my shoulder, a yellow metal 2d Lieutenant’s bar on my right collar. I still had a set of metal crossed rifles – denoting Infantry – on my left collar which I got at West Point before graduation. An obvious ‘new guy.’ As soon as I could I replaced the crossed rifles with crossed Sabers – after all we were the 7th Cavalry, right? Even if we fought as Infantry. For heraldry and military tradition of famed units are kept as much intact by the US Army between wars. Soldiers are known by the Units they have served in.

At this time in that War, officers were still wearing metal insignia on their uniforms, rank on one collar, branch of service on the other. As well as on soft caps or, as in Korea, ear-flap pile caps as protection from the cold. It would be some time before those important symbols of rank were made of cloth, and dark - easily recognizable by other soldiers and officers up close, but not an inviting target by North Korean snipers. who knew well enough if they kill the leader, the unit will be weakened.

New Mission

The purpose of Flynn's meeting was to inform the Company that the Regiment had new orders, and it was to move into a forward assembly area further north, and prepare to go on line with other units to halt the enemy advancing. For the 8th Cav Regiment had been in contact with a new enemy force as it reached Unsan, and had taken tremendous number of casualties, one battalion was virtually overrun, and many prisoners were taken by the enemy. The new enemy seemed to be Chinese. We were also to watch for lost American soldiers scattered by the Chinese assault. We were to get ready to move out in 1 hour.

That was the first time – November 27th, 1950, that I heard the term ‘Chinese’ instead of ‘Korean’ with reference to the enemy in front of us. The entire world would know it soon - that China had massively entered the Korean War, and crossed the Yalu River international border to oppose the United Nations forces, especially the American Army and Marines.

I returned to my 2d Platoon area and passed the word. Sgt Ingram translated it into specific orders to everyone in the platoon. There were no upbeat faces or comments from my soldiers when they heard the news of their new mission. For this had been their only really good break in months, MacArthur had promised all the soldiers home ‘For Christmas’ it was getting damned cold, and now the 7th Cav was going back ‘into the line’ of fire and combat action, against a new enemy.

My Platoon's History

While we were waiting, after our 30 man platoon (which was supposed to have 40 men) got packed and ready to move out on trucks, Ingram and I talked. I learned two important things.

I learned that Captain Flynn had relieved - fired - the previous 1st Lieutenant, 2d platoon leader. I was his replacement. Sgt Ingram didn't venture an opinion why he was relieved and I never found out.

Then Ingram said that the 2d Platoon was not too well regarded by the rest of the company officers and NCOs. I asked why.

Ingrams’s answer surprised me. He said that at least half of the platoon were jail birds. That when the rifle companies at Fort Benning, Georgia were ‘levied’ to provide so many soldiers with such and such MOS’s (Military Occupational Specialties), to fill up what would become a newly formed 3d Battalion, 7th Cav which would be shipped to Korea, some company commanders - whose units were staying on at Benning - were understandably reluctant to provide their best men. They attempted to palm off their worst. So they went to Judges in Columbus, Georgia who were responsible for jailing their men for minor to more serious charges, and asked if the Judges could give their men a choice – stay in Jail or go to Korea. Several judges obviously agreed to make the offer.

So the Korean War helped empty the Columbus, Georgian and Phenix City, Alabama jails. And the 3d Battalion, 7th Cav, got a bunch of soldier jail-birds.

Then, over time, within Company K there seemed to have been requested shifts in men from one platoon to another, which is not unusual when men want to be near their buddy, or to get out from under an NCO or officer that they can't get along with. So the 2d Platoon was not left with the best men. It had become the "Jailbird" platoon.

It became clear SFC Ingram and I had our work cut out for us. I was faced with my first 'commander' challenge. I wasn’t about to follow in the footsteps of my predecessor lieutentant who was fired.

I didn’t know much about field manual Infantry combat yet, but I knew quite a bit about leadership. I had spent the last 4 years at West Point learning it.

Next Korean War (3)

- Details

- Written by dave

- Category: Korean War

- Hits: 7293

Blocking the Chinese

The 7th Cav moved out from its Army Reserve position, near Kunu-ri the end of November toward and into the new ‘assembly area’ to the North behind the 8th and 5th Cavalry Regiments who were still‘on the line.’ With truck shuttles it took all day and into the night to reach the ‘assembly’ area it was ordered to occupy.

Information and Rumors began to fly. While on the move K Company – including me – could not hope to keep up with the ‘news’ or what the current situation was around us. The ‘Fog of War.”

There was no question now that the Chinese Army was massively on the move. China was in the War in a big way, replacing the defeated and dispersed North Korean Army. And it was coming due south to and through the 1st Cavalry Division and the adjacent – to the east - 7th Infantry Division. And it was attacking the Marine Expeditionary Force that was north east of the 8th Army, driving it toward the sea. In between had been the II ROK (Republic of Korea) Corps that the Chinese hit in large force shattering it.

The threat was obvious – split the UN army, drive south and trap the 8th Army major forces, including the 1st Cavalry Division.

Rumors abounded about the 8th Cavalry having had an entire Battalion overrun. In fact the 1st Bn lost 15 officers and 250 men, the 3d Bn ceased to exist, and in all the Regiment lost over 800 men the first week of November killed, wounded, or captured. In fact Cav units following up behind them found many soldiers trying to escape to the south toward our 7th Cav after their units were overrun or bypassed. Three soldiers were found dead in the main road north, executed with their hands tied behind their backs. An indication of how the Chinese were likely to fight.

My first mission, while our 7th Cav was on the line, was to take out a patrol and see if we could rescue any American soldiers who had escaped from the 8th Cav bloodletting. We found none.

While it was years before I learned all the facts, two of my West Point classmates, one of whom I knew later - Mike Dowe - was captured when a battalion of the 19th Infantry Regiment, 24th Division was overrun, and Mike was a POW for 3 years. In all, 40 of my Class of '50 Classmates were killed in action during the Korean War. The highest number of any class which served in that war - or any other war.

It was also at that time that a Catholic Chaplain, Fr Kapauan who was in the 8th Cav, refused to escape to the south when the units he served were being overrun. He chose to stay behind, tend the wounded, give last rites - and be captured himself. And he died as a Chinese prisoner of war, never giving up his faith. His bravery and devotion were so great, that, urged by fellow POWs after they were released in 1953, Chaplain Fr Kapauan was, in 2014 awarded posthumously, the Medal of Honor, by the President himself. He remains the only Military Chaplain who was awarded the Medal of Honor in all American Military History. Mike Dowe, (my classmate) in the Prison Camp, observed Fr Kapauan's strenuous efforts to help his fellow soldiers to survive - in body and soul. And he aided in the recommendation for award.

Thus by December 1950 the 7th Cav went, now formed as a Regimental Combat Team, with its own Armor and Artillery, started into what can only be described as a ‘Blocking Position’ astride the invasion route at Kujong-ni. But that was soon changed to protect the east flank of the 8th Army at Pukchang-ni since the ROK units were collapsing to the east, and the Chinese could come around behind or flank US Units.

I only had fragmentary information that painted the alarming situation. And no maps. Originally the only maps of such areas were Japanese maps. It took a long time before the Army Map service was capable of getting 1:50,000 scale maps with readable information to the units. We were flying partially blind, so to speak.

Dante’s Inferno

Company K and the 3d Battalion moved into position behind the 1st and 2d Battalions to act as a counterattack reserve force. It was dark. I looked to the north where there were mountains between us and the Yalu River, just over those mountatins.

Every mountain within sight had a Ring of Fire around it! About a quarter to a half way up. That was a stunning sight – and memorable. It was Dante’s Inferno all over again in this godforsaken place called North Korea! And I was in Hell.

The Chinese had set those fires to burn out the South Korean units defending those hills.

Whether it worked or not, I never knew. But I was struck with the extent the Chinese were willing to go to win – decisively, once its mass military power was unleashed.

Then I set to the task of insuring my soldiers were digging in to await the inevitable attacks against us.

Refugees as Cover

Another problem emerged that made movement along the roads very difficult as the Chinese Armies advanced. CIVILIAN Refugees. Thousands upon thousands of refugees fleeing. Even though they were North Koreans, they feared the Chinese. So fled south.

Controlling them was nearly impossible. Closing Check Points to stop them clogging the roads so American units or trucks had to pass didn't work. They just streamed by by moving away out into the fields and flowed around the checkpoints like water.

Worse, both Chinese and North Korean agents took advantage of that flow, and concealed themselves as Refugees to sneak through while carrying under their clothes weapons and ammunition and weapon parts. All of them could not be searched - too many. Those few discovered with such, were detained as prisoners on the spot.

Few Americans understand that such a tactic - as infiltrating agents and armed soldiers dressed as civilians has been a cardinal strategy by Communist and then later Islamic insurgents forever. Americans would 'never do that.' For several reasons - we bend over backwards to not risk or impersonate innocent civilians. We don't hesitate to use CIA agents and their contract locals to 'infiltrate' into foreign countries or areas controlled by them. But we do that strictly in accordance with US laws that limit what such government agents can, and can't do - such as carry weapons or explosives to kill, not only enemy government persons and equipment, but also innocent civilians - the latter for the purpose of intentionally either causing an propaganda 'incident' or to terrorize the populace. (That's called "Terrorism" if you missed the point.)

That tactic had been used earlier - in July, when the 2d Battalion of the 7th Cav was just moving inland from its landing craft from Japan, the North Korean Army was still attacking and moving south through South Korea. The North Korean agents not only 'infiltrated' into the rear areas, they sometimes fired on green 2d Battalion soldiers from the roadway, and prodded soldiers to fire back, hitting many innocent civilians and creating the No Gun Ri INCIDENT, that the clueless press loved to report on.

It was just that scenario that triggered a reporter 60 years later to interview some old South Korean civilians, many communist who lived in the area, who claimed, in 2006, there had been a civilian 'massacre' by US soldiers at No Gun Ri, South Korea, in July 1950!

One savage incident happened to the 7th Cav during our December retreat from far North Korea. As refugees piled up at a Check Point the 29th of November, a Lieutenant Sheehan, Company E Commander of the 2d Battalion tried to go forward of his check point in a jeep into the crowd with an interpreter and a bull horn. He got up on the hood of his jeep with the interpreter, a South Korean soldier who spoke some English and started to reason with the crowd. Either a Chinese or North Korean 'agent' from close inside the crowd tossed a grenade onto the jeep. It went off, killing Sheehan, the interpreter, two other US soldiers at the jeep and several civilian refugees close by.

The Chinese didn't give a damn what civilians they killed also. They used such opportunities as an excuse for a propaganda incident, to try and paint American soldiers as civilian killers.

The profound difference between Chinese soldiers and their Communist leaders, and Americans and theirs, are the differences as to who goes out of their way to avoid harming innocent civilians. And make restitution if they do. American's follow the internationally agreed to - as in the Geneva Convention - Rules of War. The North Korean, Chinese, and Soviet governments do not follow such rules.

So throughout the Korean War, that difference was apparent to me in my first war.

|

|

| Bitter Cold Field Conditions, the Winter of 1950-51 |

The Frozen Retreat

Then came a grueling 200 mile frozen foot marching Retreat for the 7th Cavalry. It had been ordered to continue to be the covering force in the western side of North Korea, as the entire 8th Army started a planned 'Retrograde' movement all the way back to Seoul.

First of all there were not enough trucks to carry all units, including the 7th, simultaneously. So men had to march, continuously day and night over the deteriorating frozen roadway and shoulders. And then periodically we had to set up blocking positions, with rifle companies trudging up to a mile left and right to extend the line so the Chinese could not easily flank even the blocking units. Then when the order was given, to trudge back down and continue the endless march southward. Sometime Army 2 1/2 ton trucks shuttled units part of the total 200 mile way south.

That was exhausting. While the temperature dipped to 30 degrees below at times. Especially in the late night hours while we had to march, and not stay in our down sleeping bags.

And Company K still did not have cold weather gear for every man.

Those damned Shoe-Pacs were issued for Rifle Company men. They were designed to keep the feet warm of men who stood around a lot - like artillerymen - cooks, or in headquarters or drove trucks and jeeps. Not for hard marching Infantry soldiers. Their felt padding got wet inside, and the frozen rubberized boots came apart at the seams from being creased constantly as men marched. They fell off the feet of some men. At least half of my platoon, already reduced to less than 30 by sickness and frostbite, had those things. And I would see some men holding their Shoe-Pacs on their feet by twine and rope.

Some Army Quartermaster genius back in the US who never saw a Rifle Squad in the field designed them and contracted with US companies to manufacture them. I am sure he got a boost in his pay for that 'invention' to solve the problem of the unanticipated Korean winter cold.

I refused to wear them. I stuck with my standard GI leather boot, as did Sgt Ingram and most other of my men, even though we were risking frostbite. I had to work hard to keep my worn socks dry when we had breaks. Even so, my feet became raw.

I appreciated what Napoleon's soldiers went through in their thousand mile retreat from Moscow. The majority of them never made it back alive. We lost some men, but US Army medics and the medical support structure of the Army really earned their pay.

I never saw a television episode of MASH 50 years later that portrayed Doctors in the Korean War which covered the frostbite problems of the 8th Army during its long retreat in the winter of 1950. Not romantic enough.

Those forced marches were brutal on all of us. And we were conscious we might be fired on from out in the dark at any time, by Chinese soldiers trying to race us south, so they could set up road blocks to cut us off. - even by 'guerilla' units formed in our rear, among South Korean civilians, who looked forward to a North Korean - i.e. Communist - victory in that war.

Even when the Japanese occupied the Korea's, there were plenty of underground communist movements throughout the country. They looked forward to defeat of the South Korean government.

The Attack on L Company Near our K Company

During one 8 hour period, Company K was ordered to set up blocking positions on the slopes of a sloping hill mass to our east, while L Company was astride the road, and M company was stretched out on the other side of the road. L Company's Command Post was right on the road, and they had been able to erect a stand up tent, lights inside it. 3d Battalion Headquarters was further behind L company, also on the road itself, where its few 3/4 ton trucks and command jeeps - 1/4 ton - were able to park next to it.

My platoon was strung out, with two man positions, up the sloping ground where the forest was fairly thick to the north of us. We started digging into the frozen ground The exhausted Commo Platoon carried wire on carrying spools with crank field telephone to my position, and the other two platoon positions and then back to Company Hq, where Captain Flynn, his radio operator and a few others where huddled. Our already flakey 'walkie talky' hand held SCR536 radios had long since lost their battery charge. So wire was the only way to communicate, other than by runner.

I thought to myself, if the Chinese come through those trees, this would be it - my first combat engagement. While I was shivering I was calm. It was about December 10th. I wondered what my mother and sisters were reading about this war, and the defeat of the 8th Army, that was retreating.

Later I realized they learned little about the 8th Army retreat. What they did read about was the Marine force retreating in another sector under our same conditions. Reporters flocked to cover them. But then the Marines always have had a big publicity machine. They get the press. So the public always publicly pitied the poor, cold, Marines. While much larger force, the 8th Army, was not even mentioned in the reports.

I started to call it a 'Second Page War.'

About 10PM, firing started down on the road, about 200 feet down below us to the left. Tracers split the air, machine guns and rifle fire suddenly opened up without warning. I never heard mortar rounds landing at first. It was a surprise attack An enemy force was ramming its way at, and through the L Company guarding the road. I could look down and see the firefight. It raged for at least 20 minutes and then the Chinese pulled back to lick their wounds and drag off some of their dead.

The Chinese had overrun a platoon of L Company, and got into the tent behind it. Several L Company men in the tent were killed, others wounded. They had not broken through the last line of defense at Battalion Headquarters with a platoon guarding it. I wondered if I should be doing anything with my soldiers, such as fire down on the road with my Platoon machine gun to a point on the road beyond where I last saw in fading light where L Company was dug in.

But I had no orders from Flynn to do that, and it just might expose my platoon to those coming through the trees. I was trying to think tactically. I did nothing, while some Americans died 200 yards to the side of me.

The Chinese never came through the trees. Quite a few rounds went over our heads, with the characteristic 'crack-thump' sound, except the firing was so close that the thump merged with the crack.

I learned a lot from that brief engagement I could hear and largely see when flashes of gunfire illuminated for a second the scene, to the side of me. The different sound of the different rifles, machine guns. And 60 mm mortar fire outgoing to where the Chinese came from along the road. I never noticed the cold. I guess my blood was churning, producing heat.

That fire fight started my realizing how much my hearing, in the dark, was so important for me to understand what was happening. And the Chinese Army almost always attacked at night, to minimize the effect of superior American firepower during the day.

I was begining to accumulate combat experience.

I don't know whether it was right then that night in my first Infantry combat experience, but I soon realized I was getting eligible for the prized - by soldiers - the blue 'Combat Infantry Badge.' For that badge can only be earned and worn by Infantry officers, full colonel or below in rank, and enlisted men, whose official MOS was Infantry (not artillery, or signal or anything else), and who were subjected to 'small arms' (i.e. rifle) fire by an armed enemy of the United States.

At the time I thought one had to be in such combat for 30 days or more, but unbeknown to me was that Captain Flynn, already had put me in for the CIB, which all his officers and men were eligible for from the first time they were fired on.

The blue field Combat Infantry Badge - CIB - with its wreathed musket - of the type used by the first Americans during our 1776 Revolution - is the most coveted Infantry badge - which implies no 'bravery' per se - but exposure by Infantrymen and Infantry Officers to direct deadly enemy rifle fire.

|

|

| The Prized Combat Infantry Badge |

Our Own Dante's Inferno

The Battalion Commander had decided to pull back along the road to set up another blocking position. The failure of the Chinese to break through and cause much more mayhem seemed to give them pause, before they would attempt again. The Regimental Commander would have had to approved. He obviously did, for the Battalion Commander put out a novel plan quickly.

The order was to use some deception. We were, now that the firefight was over, to start bonfires - out in front of us far enough that 60mm mortar fire would not hit us. Americans are famous for starting warming fires at the drop of a hat..

We were to start bonfires AS IF they were warming fires. And to move around as if we meant to stay.

THEN, at exactly 1 AM and as quietly as possible slip back and away, down to the road behind where L Company still was, blocking the road. And the entire Battalion would then march hastily south, toward the next blocking position.

I remember taking one last look at the 10 or so 'warming fires' still crackling - with nobody around them. Our own Dante's Inferno.

IT worked. we were miles further south before the Chinese, planning their next attack, woke up to the fact there was nobody there to attack.

Two can play with fire, not just one.

We continued on our retreat.

Next Korean War (5)

- Details

- Written by dave

- Category: Korean War

- Hits: 5196

The 3d Battalion ‘Edge’

This is a good a place to tell why the 3d Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment, in which I was to serve the rest of my year of combat in Korea, was a little different from the ‘older’ 1st and 2d Battalions. And from a number of standpoints had an edge on the other two battalions.

Now Infantry Battalions, whether they were in the 1st Cavalry Division, or the 2d, 25th, or 7th Divisions that also served in Korea, are pretty much identical – in organization, manpower, equipment and weapons, and distribution of skills among the 1,000 officers and men Each had three 200 man Rifle Companies, a Weapons Company, with Heavy, Watercooled 30 caliber Machine Guns, and 81mm Mortars, and a Headquarters Company. 5 Companies. Each, when they were available, headed by a Captain.

Infantry Regiments – such as the 7th, 5th, and 8th Cavs are also usually similar – with 3 Infantry Battalions, a Heavy Weapons Company with larger 4.2 inch mortars, 75mm Recoilless Rifles, and heavy, water-cooled machine-gun sections, and usually supported by an Artillery Battalion with 105mm Canon to support the units of the Regiment.

But the conditions of training, equipment and leadership, of those ‘Regular Army’ units that exist at the outset of a war can greatly influence their success or failures and reputation – at the top, and among soldiers.

Post WWII War Deterioration

When the Korean War broke out – as a huge surprise to Washington, as well as the American Public – on the 25th of June, 1950, both the Truman Administration and the Congress had, from the end of the War with Japan, let the Army deteriorate. Equipment was not modernized, troop training – which costs money - was de-emphasized. And manpower was reduced. In the Occupation Forces in Japan by 1950, including the 1st Cavalry Division, had their fighting strengths reduced by fully 1/3d.

Now the method the Army command used to meet the Administration reduction of strength ordered was to cut one 1,000 man Battalion out of all three 1st Cavalry Division Regiments. That reduced them, including the 7th Cavalry – which had the honor bestowed on it by Gen Douglas McCarthur – of leading the 1st parade in Tokyo after the surrender of the Japanese – to a two battalion 7th Cav Regiment. The 1st and 2d Battalions.

Now that is more than just a matter of 1,000 men less Regimental over all strength. Its screws up the ‘triangular’ tactical organization the Army was based on and had succeeded brilliantly through WWII. In turn that is based upon the judgment that, while two squads per platoon, two platoon per company, two companies per battalion, two battalions per regiment, and two Regiments per Division fight up front, one third should be held in reserve until the critical action demands its intervention – such as the last push to victory over a more linear enemy. And a way to give soldiers in 1/3d of the command a break from heavy combat.

The 3d Battalion to the Rescue

So for manpower savings, the 7th Cav had only two Infantry Battalions in each Regiment when the war broke out. As it was ordered to get ready to intervene in South Korea where the North Korean Army had already overrun the South Korean Army and mauled the first US Units of the 24th Division that were thrown in, a Third Battalion was needed. To bring the 7th Cav up to full designed strength.

The Army ordered Fort Benning, Georgia, to organize a 3d Battalion, 7th Cavalry in manpower, equipment, leadership and prepare it for shipping. Because the pool of officers at Fort Benning was large, the Chief of Staff of the Army was able to handpick the Battalion Commander – Lt Colonel Jim Lynch, West Point Class of 1938, who had commanded a battalion in WWII. He was a proven leader.

Lynch in turn selected his staff officers and four company commanders, Captain Flynn, Class of 1944 among them – for Company K - who had been teaching Infantry operations to officers at Fort Benning, and was well ‘up’ on tactics and operations.

That 'new' Battalion got in a little badly needed unit training under experienced officers before it left for Korea.

So by July 23, 1950 the 3d Battalion arrived at Fort Stoneman, California, embarked with all its equipment, and sailed for Korea, arriving as a unit in Taegue, South Korea by the 26th of August to join the 7th Cavalry as an integral and badly needed, but untested, ‘3d’ Infantry battalion.

It even trained - took classes - on the troop ship that brought that Battalion to Taegue, South Korea. It never landed in Japan

The Problems for the 1st and 2d Battalions

While the 1st and 2d Battalions, having been occupation troops in Japan, had a large number of their WWII experienced NCOs stripped from them to reinforce the battered 24th Division already in Korea. So their commanders and staff were just from those remaining in Japan. Their units had not been able to do any serious Infantry across-ground training in Japan for two reasons – they were not permitted to cross rice paddies badly needed to be planted for an national economy in shambles. And a severe set of storms had drowned much arable land. They were just 'occupation troops' forced into combat service in the southern portion of South Korea before they were really combat ready.

It was that combination of circumstances that led to the breakdown of control in the face of the swiftly advancing enemy, the retreating refugee civilians, mixed in with clandestine North Korean agents green US troops, all of which led to the Nationally publicized Incident at No Gun Ri, that 50 years later was branded a ‘massacre’ by the second-guessing US Press, which had most of its facts wrong, even though its reporter got a Pulitzer Prize, who was aided by a fraudulent, lying US Soldier whom the press - including NBC's Tom Brokaw - relied on, and who eventually went to jail for defrauding the US Government. It was the 2d Battalion, 7th Cav which became the fall guy. I never forgave Brokaw for never, on air, apologizing to the officers and men of the defamed 2d Battalion.

Suffice it to say that the newly formed 3d Battalion of the 7th Cav retained an edge in operational success from the day it landed, until the entire 7th Cavalry was as part of the 1st Cavalry Division were pulled out of Korea in December, 1951 once the Truce Talks stopped major military operations by either the US-UN or the Chinese.

But all three battalions and the Regimental Headquarters, got their baptism of fire, and plenty of combat experience during the touch-and-go defense of the Pusan Perimiter from August to October.

So I was privileged to be part of the best Battalion of the 7th Cavalry during its most trying times to come - against the very large and not defeated - Chinese Army.

Next Korean War (4)

- Details

- Written by dave

- Category: Korean War

- Hits: 5107

My Real Infantry School

Our retreat - which was destined to continue through December all the 200 miles back to Seoul, South Korea, with our Company K soldiers road marching at least 100 of those miles in the dead of winter - was a real test of our Army, and my 'platoon level' leadership.

The pattern kept being repeated - 15-20 miles marching while carrying full packs, with rifles - M1's, Browning Automatic Rifles (BAR) and one squad carrying a machine gun and its ammunition passing through a blocking unit, then being trucked for perhaps 20 more miles, dropped off, where we set up a temporary encampment out in the open, soldiers eating their C-Rations and resting all night. Some times being a being a blocking force while other companies passed through us. Then repeating the cycle. It took over 20 days to arrive north of Seoul, and the Han River south of the 38th Parallel border, while staying ahead of the Chinese Army, whose infantry soldiers were suffering as much as we were. And they did not have down sleeping bags.

But there was a repeated nightly gathering that became my REAL Infantry School - the one I and all my West Point Classmates from '50 didn't get before being thrown into the Korean War. That took place at an early or later time to eat, after the Company was looked after by we leaders - sometimes making our men take off their boots and socks so we could check the condition of their feet and order remedies from our Medics for men whose feet really looked bad.

Captain Flynn would have all we platoon leaders together, sometimes with good heat, sometimes not, but always with Coleman Lantern Light and we inside a blacked out abandoned Korean Hutch abandoned by its owners. We would heat up and eat our C-Rations (and sometimes when rations were short and all the men could not be given a canned C-Ration, I ate local rice stirred up as Korean dish named 'Go Hung'. which gave me intestinal worms for years afterwards)

There was no mail from home reaching us during the retreat. When any did arrive, it came in bunches.

I had no letters from home yet. Though I sent probably 4 or 5, including to my sisters as well as my mother. I knew they would be intensly interested in, and fearful of what I was going through.

But the memorable 'fireside' chats (sometimes with no real fire to watch) were led by Flynn who talked to each of us in turn learning what went on of importance that day in our platoons, and listening to recommendations from each of us. Then Flynn would explain another valuable 'tactical' lesson, usually pertaining as to how to fight the Chinese units - the craft and art of Infantry war. He would add some general comments on the general war and our situation, with what he learned from the Battalion briefings he attended also.

I soaked it all up. One very striking recommendation - to use 'marching fire' in the assault more than 'aimed' fire - stuck with me. I had never thought of it, nor really knew what substituting volume for accuracy of fire could accomplish.

I did remember back at West Point in one Military History course reading S.L.A. Marshal's "Men Against Fire" researched in WWII. In which he pointed out that, for a variety of reasons only a FEW men actually fire their rifles in combat. That was a surprise to me when I read it. But Marshal had interviewed many men, NCOs, and officers in many Rifle Companies in Europe.

The reasons were many. Some men didn't want to 'give away their position' by firing. Some couldn't settle down and aim at a man-target, because enemy men would be ducking and bobbing around, as well as shooting back. Some were just so rattled and frightened by the battle they literally forgot what they were there for. And a few, very few,couldn't bring themselves to shoot to kill another man, even an enemy.

Flynn pointed out that the American Army had for too long stressed making men go to a rifle range, and shoot at stationary targets all day long. Pursuing only 'accuracy.' But combat is not a series of stand up and wait targets, but fleeting figures shooting back, who can be intimidated by the deady crack of incoming fire.

What was the antidote? Flynn said 'use marching fire' - get everyone to fire at the outset of an assault at the area where enemy soldiers are likely to be, even if hidden, and keep it up while the attack lasts. He pointed out that the US Army can afford the expenditure of ammuniton (while many other nation's Armies cannot). That massed fire is a US Army strength. Accurate fire is not. That is a job for Snipers and those few soldiers who - usually from their early years on farms, ranches, or hunting - learned to fire very accurately.

THAT lesson not only stuck with me but became my salvation months later in a very harrowing operation. Its application was so significant in the success of one of our missions against superior Chinese force holding a dominant hill, that that I wrote it up after I left Korea while teaching at the Infantry School in Fort Benning. It was published and featured in the Army Combat Journal as "Surprise and Marching Fire"

I was beginning to find my writing tongue in the first two months of my being immersed in the hard combat actions of the Korean War. For I had something of importance to say. About life and death, tactical military matters and human drama, and even about the philosophy of war, and of the obligations of leadership.

My Bahavagad Gita

Now I can't remember where or when I got my copy, or why I carried it with me in my back pack. But I started, almost every night when we had light and fire, to read versus from the Bahavagad Gita. The sacred 700-verse ancient Hindu epic.

To this day I am not sure why I started reading it. Being in the Orient? Looking for some solace from something else that Army Field Manuals? Or because it was, I knew from my general West Point education, was one of the great philosophical and literary works of the world. In a very small book, easy to carry in my backpack.

I did not carry a Bible. Or any other reading material.

And I wondered, if I were killed in action, what the report back would say, or what my family would think when my 'personal effects' came back to them, and the Gita was there.

But I read it and part of my mind dealt with the greater philosophical issues of the war we were in.

I was beginning, in my mind, to compose ideas that I wanted to write down. All I had was a pencil and a little paper. And was about to start scribbling when, if ever, this retreat would end.

What If We, Like Custer, Are Surrounded?

Then in one of these nightly meeting, Captain Flynn told us two things.

What we should do if he were killed, wounded and evacuated, or captured what should be the the chain of command when he is gone. Who does he want to be first in command, second, third, and fourth, after he?

Both his answers stunned me.

First, if we are surrounded, cut off, and he is out of action, for us to head NORTH, not south in the direction the Chinese were moving. Reach and cross the Yalu River, get across Russia - Siberia - and come out in Europe. Try for occupied Germany!!!

Secondly, after him, if he is gone Flynn wanted Lt Shanks to command the company, then Lt HUGHES to command, then Sgt Abaticio.

Even though 1st Lt Ryan was the Executive officer and higher in date of rank (which decides who ouranks whom when both officers are the same rank) than all the others except Captain Flynn, he was back at the Battalion Trains area, where company mess - cooks and stoves, supply, including weapons, and administration where the Morning Reports had to be filled out and sent on. If things got that bad in combat up front, it would not be clear he would even be able to get to the fighting elements of the company to take over. Someone on the ground had to take command until the immediate combat actions were over, and the normal 'chains of command' based on seniority, starting with the Battalion Commander could decide who should command K Company from that point forward.

So I was 2d in line, in case of loss of Captain Flynn.

The full weight of the possible burden of 'command' in a war we were losing, by retreating, became apparent to me at that instant. I was really surprised Flynn had that much confidence in me after only one month in combat, during which I was in several minor actions, but also what a responsibility that would be -Commanding 200 men, the ENTIRE K Company command - the rifle platoons, the weapons platoon, the headquarters, the other more junior officers - everything - having not recieved even the Infantry Officers Basic course at Fort Benning before being thrust into combat.

Young, inexperienced men die in war. or fold, while some grow. In the eyes of my Company Commander John Flynn I obviously was maturing as a combat leader.

Next Korea (6)

Page 1 of 3