The Deadly Patrol

As both the Chinese and American forces west of Uijongbo and east of the Imjin River glowered at each other from June through August of 1951 both sides kept sending out patrols to keep track of what either was doing. There were inevitable clashes between patrols.

I didn't like having to dispatch patrols repeatedly toward areas I knew would be defended well and where ambushes would be set up just to kill or capture American soldiers for which this inconclusive war had gone on too long.

I was getting new soldiers and several new officers into my Company K, 7th Cavalry. I wanted them to get used to each other before sending them out into sure trouble.

So, even though I was company commander, I decided to send out the next platoon sized patrol myself with two combat savy NCOs, to see if, with our greater experience I could avoid trouble - and casualties - while getting the intelligence Battalion demanded.

As it turned out, we encountered trouble, and only avoided more because by then I knew how to calculate time-of-flight of our artillery shells by sound alone - which I have written about before - I came to rely on my ears more than my eyes to track a battle.

We moved out on a rainy morning, first about 1,000 yards west, then started south along transverse ridge lines where the enemy could establish observation posts to look more closely at our 7th Cav lines and forces,

We were moving, as usual, in single file, and quietly, on that narrow ridge, about 30 yards between our 'point man' - the most detested position, for its the first soldier shot at, and his squad leader. I was behind the squad leader.

There was burst of fire from what I knew were Chinese weapons, and rounds popped over our heads. We fired back, but the enemy was down in foxholes. Could have been ten or more Chinese in those holes, judging from the amount of fire aimed in our direction. We were below a rise in the ridgeline so we were not line of sight to the enemy. But everybody hit the deck. I crawled up to where the squad leader was. He didn't need prompting from me. He said "Cornell is dead." They have foxholes on both sides of the ridge. They are still in em"

I crawled past him, stuck my head up to see the soles of Private Cornell's boots as he lay on the ground, not moving. I saw enough blood on the back of his fatigue shirt to know he had been riddled with bullets. I could also see just the tops of several Chinese heads in the foxholes just beyond him maybe 10 yards. They let him get that close before opening up.

Where Experience Counts

I knew he was either dead or so close to it, getting him back was a near impossibility. I would have to assault and overrun all those herringboned foxholes that were on the high ground, and take more casualites over 1,000 yards to the closest friendly lines. And we had found what we were sent for - intelligence on the nearest Chinese positions.

But I also really wanted to get his body back. I didn't want the Chinese stripping his boots and clothes off, getting his rifle and ammunition, and leaving him to rot on the mountain. I couldn't remember when we ever failed to get our dead back, even if it was days after the battle. But I also did not want to get even more men hit trying to get him.

So I decided to try something only my long experience hearing shells pass overhead and explode could tell me. I already had noted mentally as we set out on patrol, the firing over our heads by the support battery of the 77th Field Artillery 105mm shells that were 'interdicting' long range, the Chinese lines in their rear. Miles and miles away. Now, having turned south we were 90 degrees to the gun target line.

I gave some quick orders to my following men to arrange themselves to be sure we didn't get flanked. Then I called in my intelligence report. I added that I was going to try and get Cornell's body back. It might take some time. That I wanted the 77th Field Artillery Forward Observer on the radio.

I told that FO that I wanted to have him order, very, very carefully, a series of fire missions short of the enemy on the ridge in front of me, then just over them by 200 yards, so we could try and reach and pull back our dead soldier while the Chinese were ducking, not knowing where the impact would be.

He got the idea, and started the fire mission with the map coordinates I gave him, while I got two men ready to try and reach Cornell and pull him back. I urged the Forward Observer - who would be flying blind this time, just relaying what I told him - to be especially careful because were were less than 100 yards to the right of the gun-target line. He understood, and told the battery to double check.

I listened to the first rounds come screaming in to the left front of us, as I watched the Chinese foxholes, and counted the time from when we heard the guns until the splash of the rounds. As I thought the Chinese in the foxholes ducked down when they heard the rounds were incoming and they knew they were aimed at them. I told the FO to adjust a little further closer to the Chinese. At least one of the 6 rounds actually hit on the top of the ridge. Good. Really puckered them up.

I wanted the two men to scambled forward on hand and knees while the rounds were in the air and the Chinese were down deep in their foxholes not knowing whether the rounds would explode right where they were.. Then wait until the next salvo was fired. and while it was coming down off to the right front of them, pull the body back.

I could see the Chinese soldiers duck down when the first two salvos landed a good four seconds after the sound of the guns first reached them and us.

So I told the FO to fire that again, and then add 200, and fire only on my command.

The guns sounded, and the two men scrambled forward in the mud in that four seconds and lay right at Cornell's boots when the rounds splashed to the right front of them but well down the steep slope, while the Chinese stayed well out of sight, expecting to be hit.

Then I gave the command to fire, the FO relayed it, and we heard the sound, and the two men dragged Private Paul Cornell back to where we were just as the rounds went off again to our right front.

Then I told the FO it worked, but now drop 150, and fire lots for effect.

As soon as the gun sounds reached us for that salvo, we started fast back down the muddy trail with four men carrying our dead man. Meanwhile the 77th Field's 105s rounds crashed down right on or near those foxholes with maybe 10 Chinese soldiers were, once our man was safely back. No way to tell whether they hit any of the holes. The odds were good, for the 77th Field Artillery dumped at least 6 salvos on that ridge where they were, as we got back into our own lines.

As we came back, I said to myself - I suppose one could call that at the Infantry School 'Fire and Maneuver' - though no field manual ever would recommend that maneuver we just pulled off.

Hillside Prayers and the Deadly Marks

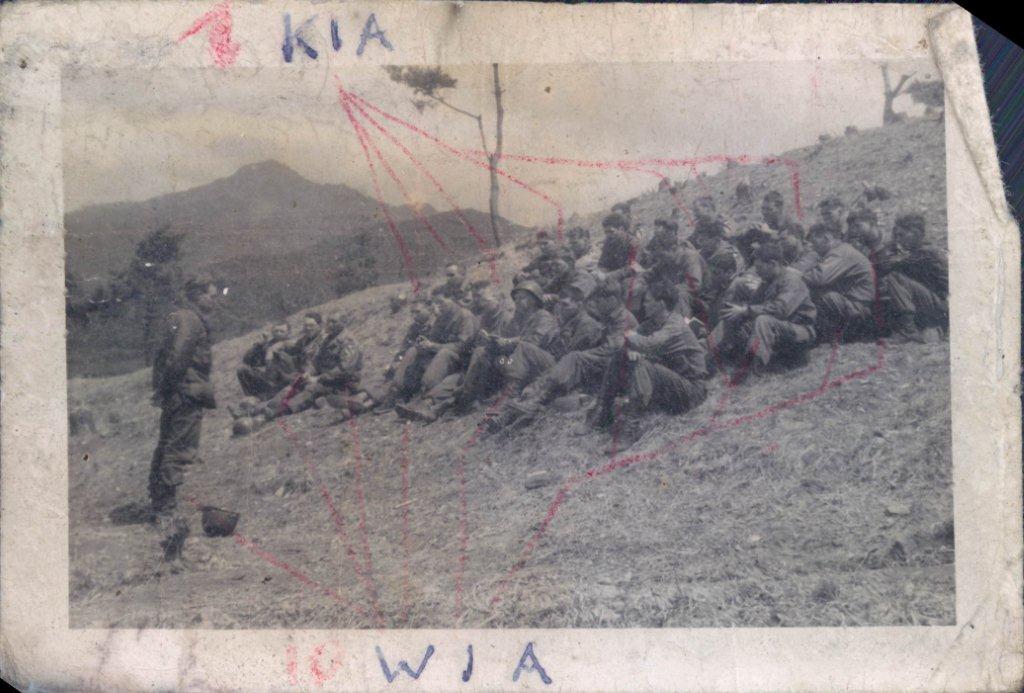

This photo is very old - it is of me holding a hillside prayer service for the platoon that soldier Cornell was in in the summer of 1951. No Chaplain was around when I wanted to do it.

But the more significant part of that photo is that I later drew lines (upper red lines) marking every man that was there that day, who was Killed in Action (KIA) afterward. And the faint lines below are of every man who was Wounded in Action (WIA) later. I studied that old photo near the end of my tour in Korea after Hills 339 and 347, when I still remembered faces. It is a photo in bad shape, but with a powerful message about the Price of War.

A sober reminder.

Emotional Aftermath

The emotional impact of losing another of my soldiers - for they all seem to be mine now that I am their company commander - got to me as I started writing my letter to Cornell's parents. I stared out at the fog and rain for a long time.

But the only way to unburden myself was to write about the incident itself and how important it was to all of us to bring back our fallen soldier. And I held that prayer service pictured above.

I did write about that mission and mailed it home to my mother. It is in the next item.