| ARRIVING AT WEST POINT |

|

|

Toting my small suitcase, I walked through the Sally Port at West Point into broad Central Area with its clock July 1st, 1946 with 922 other new cadets, some of whom came up by train from New York.

|

|

| New Cadets Arriving from NYC by Train |

I had never been ‘back East’ and marveled at the luxuriant vegetation in the middle of the summer, especially as contrasted with Colorado’s.

Immediately the upper classmen on what is called the “Beast Detail” pounced on me and all the others as they streamed in yelling at me to lock my heels together, drop the suitcase, look straight ahead (not at them), start barking out “Yes Sir, No Sir, No Excuse Sir” in response to any order or question. And do so in a very strong voice or else I was ordered to speak louder and louder. To push my chin way back until my head appeared as a ram rod extension of my neck. While the upperclassman before me, wearing white cotton gloves, perfectly fitting uniforms, spit shined black shoes, with military caps whose brim came down just above their eyes, steadily with a look of great determination into my eyes, also walked around me looking me up and down head to toe while he gave me orders.

The Central Area reverberated by all the yelling by the cadre and answering “Plebes.”

I got a sense of the ‘perfection’ demanded at West Point when one upperclassman looked closely at my eyes. In my case the pupils are half covered by my upper eyelids – which some girls said gave me an unintentional ‘bedroom eyes’ look. But the Upperclassmen were not interested in that interpretation, they wanted me to move my eyeballs, or widen my upper eye lid until the pupil was perfectly centered in the middle of the eye. Not possible for more than a momentary effort, for I was built that way.

Soon after a consultation between two of them in front of me they decided that was the way I was constructed, and that I couldn’t be expected to walk around artificially wide-eyed. And so they would let nature take its course.

But as soon as they started instructing all the plebes how to salute – the palm with all five fingers perfectly flat extended from the arm, thumb next to the fingers and not sticking out, another cadet noticed that the fingers of my right hand were not perfectly aligned when I held the salute. After much ineffective instruction telling me to get my fingers to perfectly align, which I couldn’t, they eventually gave up after I came as close as I could to the ‘perfect salute.’ I have a slight genetic defect in that hand, that pulls my middle finger over to the right away from my index finger. Try as I might I can’t make all of them nest together like I can my left hand.

That may be why I always, from the earliest I can remember, more naturally held a gun to fire with my left, not right, hand. I favor my left, even though I am ‘right’ handed in every other way.

So while West Point aims at physical perfection and symmetry of its cadets, it tolerates slight deviations. I was not the Adonis of their dreams.

| New Plebes on Day of Entry to West Point |

|

|

But they try. Together with hammering away at how cadets stand – posture – the fit of their uniforms, the angle of their caps they get close. And the one major thing they can’t control – height – they solved that for the first 150 years by ‘sizing’ all the cadets and assigning them to 24 100 man companies by height. So all four years I was to serve with 25 of my classmates in Company ‘F-2’ along with 25 plebes, 25 sophomores, 25 juniors, 25 seniors – all of whom were within a quarter inch in height of all others and me. And then the Companies ran from A-1 – the ‘flankers’, all well over 6 feet – to M-1, the ‘runts’ – the shortest cadets in the 1st Regiment. And A-2, the shortest to M-2, the tallest, in the Second Regiment, where I was, in F-2 company, for all four years.

That is why when Cadets are on Parade, whether on the Plains of West Point, or the streets of Washington DC, together with their marching synchronization their symmetry was for so long so impressive.

Such uniformity has its long understood military value – for it reinforces the sense in all men subordination of the individual to the military teamwork with others much alike – forging very close bonds between men at war.

However by 1959, that perfect symmetry was broken. Cadet Companies are mixed height. ‘Perfect’ parades of male West Pointers will never be seen again. Especially with the admission of women cadets into the Corps. Nor, in my opinion, will such a perfect military band of brother’s unity on the battlefield ever be achieved again either.

Now ‘Plebe Year’ is intended deliberately to be hard – physically and mentally. The purpose is for upper classmen – all of who went through it themselves – to ‘break down’ the new cadet until he is reduced to the common denominator of all plebes, in which exaggerated egos – whether from prior academic or athletic ability, parents status or wealth (or military rank) or from the knowledge that just to get be admitted to West Point is a real honor in itself – are wiped away by the immediate challenges. The 4 years I was there mid century, plebe life was not as harsh and tyrannical as what cadets endured around the turn of the century in which real injuries were incurred, nor as ‘soft’ (in my opinion) as cadets have it now – wherein being yelled at is greatly discouraged.

And it started out hard for all 922 of us – a number of whom already had given up by the end of the first exhausting day. We learned the basic movements in ranks – left face, right face, about face – in exacting detail. Carried our bedding, and starting uniforms to our assigned plebe rooms, 3 to a room, arrayed around the perimeter of Central Square in buildings that date far back into the 1800s.

Then in the blink of an eye all new cadets got their first hair cuts. Shorn locks lay all over the floor around the scores of barbers organized for the mass shearing.

Then started the first of the memorable “Clothing Formations.”

It is a given that soldiers have to be able to get up, get dressed, get their rifle and be ready to fight as fast as possible. But West Point’s ‘Clothing Formations’ brought the training for that Plebe training to a high art.

All plebes standing motionless in groups of ranks in Central Square are suddenly ordered to change their civilian dress to Blah, Blah, Blah - with this article of uniform, and that – all delivered in a rat-a-tat voice the Plebe has to remember verbatim, and then ordered ‘Dismissed!’

Every cadet then has literally to run into the barracks, up the stairs, to their new rooms, as fast as possible find and change clothes to the uniform ordered, from the new cadet high-collar gray to more informal, with white shirts - then dash back down the stairs out to the ‘ranks’ and be standing in ranks perfectly still - and perfectly dressed. And do it as fast as possible – in competition with all other plebes. Make one mistake and the plebe is ordered to run back to his room, correct the error, while all the other plebes remain standing at attention - until everyone is there, perfectly outfitted.

That drill repeated with different combinations of uniform each ‘session’ until everyone can perform in the least number of minutes - usually under 4, even with the crowded stairs. At least one such session every morning and afternoon for the first several days. Of course the tardiest plebe into ranks or one who has the wrong combination, is hazed unmercifully. And may have to repeat it all in a humiliating rank of 1.

The technique really works, and by the end of such ‘training’ every plebe is able to undress or dress, individually, in 2 minutes flat. I have never outlived the effects of those exercises – all my life I dress very, very, rapidly. Even when there is no enemy about to decend on me. Just the tyranny of the clock.

Late in the afternoon that first day all 922 of us less those already who have quit and simply walked away, never to come back, in identical uniforms, were marched in solid ranks – all the while being yelled at for the slightest mistake, along Thayer Road to Battle Monument which, with its Civil War canon and monuments, looks for the first time at the stunning view up the Hudson River to the north .

All the plebes are formed into a large rectangle of smaller rectangles in credible beginnings of military order, to be sworn into by the Oath of Office. Making the plebe legally thereafter a military person and subject to all its orders, and military law, including Court's Martial.

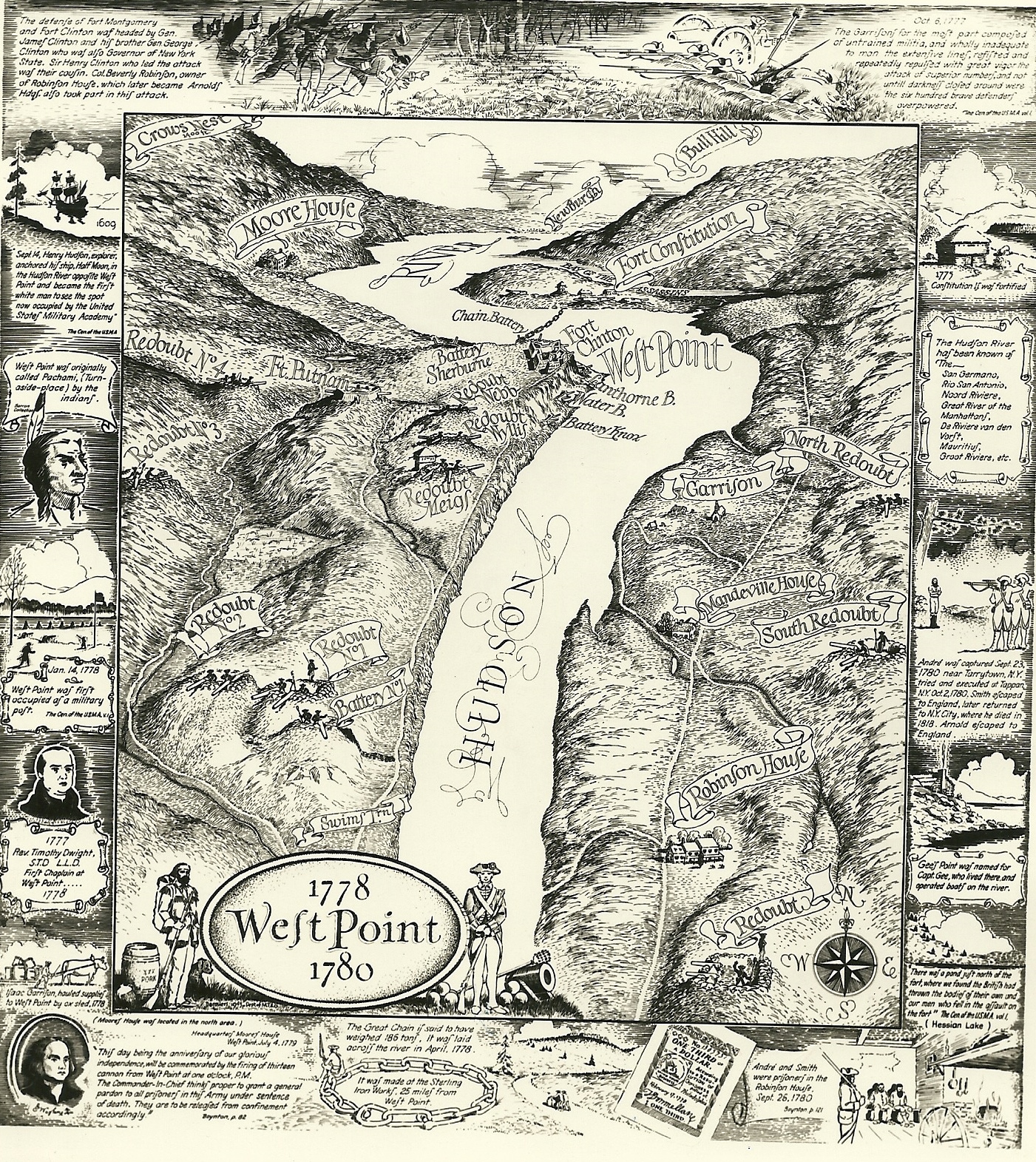

Standing there was my first fleeting glimpse under the trees on Trophy Point of the beauty of West “Point” with its solid mass of granite under us thrusting out into the Hudson River - the 'point' in West Point - that I later learned – and had to master as part of plebe ‘poop’ – that it was that granite mass thrust out into the Hudson River that forced the river to do two 90 degrees changes of direction greatly narrowed that made it the most formidable Fort during the American Revolution.

For the British knew they could never sail around that point without being blasted to bits by cannon firing down on them from the hills on both sides of the river as they were forced to tack back and forth in the narrow channel.

There was even a huge chain fabricated, several links of which are displayed at Trophy Point still, that floated on heavy logs stretched across the river at its narrowest point. The Great Chain and West Point was never tested. Thus the British, with the most powerful Navy in the world and which could control waterways virtually everywhere never could reach Albany up the Hudson and thereby split the Union.

That is why George Washington deemed West Point to be the most important military fort in the Colonies. And he repeatedly visited it, including right after Benedict Arnold tried - in an act of treason - to surrender it when he commanded West Point.

|

|

After those few minutes on hallowed grounds, solemnly swearing our allegiance to the nation, and that we would dutifully obey the orders of those appointed above us. we then all marched back to the barracks to continue getting organized in a whirl of orders and requirements, and incessant ‘corrections’ by the upperclassmen who hovered around like bees.

By evening we were all in auditoriums while an upperclassman precisely explained the Honor Code – “I will not lie, cheat or steal, or tolerate one who does.” It’s that last clause that shakes up many people – ‘ratting’ on another cadet. But over the next four years, more than one cadet was discharged ‘For Honor’ because he did not report a fellow cadet – usually a roommate – whom he knew was cheating.

Plebe indoctrination into West Point – our ‘Basic Training’ so to speak would take two months before academics started. It was extreme physical exertion, mastery of a lot of lore from what was called ‘Bugle Notes’, intense training and incessant ‘corrections’ from the cadet cadre. Part of the training was right there at West Point – inside the cadet areas, close by athletic fields, much out on the grassy ‘Plain’ where parades were held, and some military training – such as Bayonet Training.

Now THAT was getting down to brass military tacks. How to put a bayonet on one’s M-1 Rifle, and kill another man with it. Using stuffed dummies mounted on wooden frames on a part of the Plain, to attack singly and as a group.

It was then I knew West Point was training for real war, whatever else it did. . Even if every one of my classmates were headed toward being Army officers, at rock bottom, especially in the Infantry - ‘Queen of Battle’ graduates had to be able to kill enemy soldiers up close and personally.

I liked that training. For it dealt with the essence of what Infantry men for whom all the support – artillery, armor, signal, engineers, aircraft – had to do finally do to win wars, such as WWII just concluded.

Bayonet training was more than physical training. It was to instill the ‘Spirit of the Bayonet’ – will to win - man to man. I wondered if I would ever be faced with that situation.

But I began to like the raw ‘Infantry’ branch of Army service.

One upperclass Cadet made a big impression on me. He was only a 'First Classman' senior, serving on the 'Beast Detail' - that group of cadets whose job it was to train the new plebes and condition them for what it will mean the next four years to be a cadet.

That upperclassman happened to be Cadet Arnold Tucker - the very same Quarterback - and effectively leader, of the National Championship Army Football Team on whose team were the legendary, All American 'Doc' Blanchard and 'Glen' Davis - Mr Inside and Mr Outside. The most celebrated players in all of West Point's football history. (I got to see them all play in the fall of 1946.)

But what really impressed me was the sheer aura and quiet force of 'leadership' Tucker exhibited with we brand new cadets. Until almost all other upperclassmen, he never raised his voice, looked steadily into your eyes, gave his orders and advice in a calm authoritative way. I knew his football reputation before I was ever a cadet. But I sensed a real leader in the flesh - whose leadership on the football field was unquestioned, but whose leadership in the Army would be, in my very humble opinion, outstanding. Except that, from his football injuries, he was medically discharged the year after he graduated after leading the Army team to everlasting glory as National Champions.

Sound Off, Mister!

'Beast Barracks' continued at an unrelenting pace. We learned, and were required, to duplicate the precise making of our beds, arrangement of our clothing lockers, the shining of our shoes, the hanging of our clothes - all while being barked at by upperclassmen whose faces were within inches of our noses.

And in turn we were required to speak in clipped, precise words, give answers to questions, or bark out repeatedly either "Yes Sir", "No Sir" or "No Excuse Sir" to almost every query or command - loud and authoritatively enough to command the attention of all within the rang of our voice.

Why were all cadets required to speak out so loudly, instead of speaking more softly? I soon learned that it had its roots in the practical needs for war. That the actual numerical size of an Infantry Squad - 9 to 12 men - was limited to the range of a squad leader's voice would carry and his commands heard when his men are spread out, under fire, in the din and cacaphony of battle.

From the very beginning of cadet training - development of one's 'Command Voice' was demanded of every cadet. And that carried right out onto the Parade Field, where, even when all 2,500 cadets were standing in ranks spread across the wide, deep, Plain, the voices - and parade commands - by all the Adjutants, and Commanders could be carried on the air and heard by every cadet in ranks. Cadets, being trained to be 'leaders' all had to be able to speak, and command, forcefully.

One upperclassman's voice in my cadet company was legendary in its power and range - George Crall - one class ahead of me. His deep, booming, authorative voice could be heard throughout the barracks and outside enough that, among almost all other 'upperclassmen' I got to know, I think I still remember 'George Crall' more than all the others.

As for me, development of my 'Command Voice' was of inestimable value when I commanded, first a 40 man rifle platoon, then 200 man rifle company in combat.

Of course long after I retired my children wince at my outspoken voice developed on the Plains of West Point 65 years earlier.

| The Portcullis of the Headquarters of West Point |

|

|

Next West Point 2